10.06.2010

A National Treasure Turns 21 (2000)

Johnny Clegg &Juluka by Annette C. Eshleman www.dirtylinen.com/linen/feature/67clegg.html

In South

Africa in 1969 the lines were clearly drawn. Blacks did not mix with whites, and

whites did not mix with blacks. But then, nothing is ever clear or easy or

straightforward where racism is concerned, a fact made even more potent by the

reality that racism was the law of the day. Apartheid cost countless lives and

destroyed many more; however, it could not prevent Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu

from forming a musical partnership which would result in the first ever South

African group to mix Zulu with European, traditional with rock, and black with

white. Now, after an eleven year separation, the pair have reunited to continue

on their musical journey.

In South

Africa in 1969 the lines were clearly drawn. Blacks did not mix with whites, and

whites did not mix with blacks. But then, nothing is ever clear or easy or

straightforward where racism is concerned, a fact made even more potent by the

reality that racism was the law of the day. Apartheid cost countless lives and

destroyed many more; however, it could not prevent Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu

from forming a musical partnership which would result in the first ever South

African group to mix Zulu with European, traditional with rock, and black with

white. Now, after an eleven year separation, the pair have reunited to continue

on their musical journey.

Nineteen sixty-nine was the year Clegg and Mchunu met. Both were 17 and eager to experiment and share their cultures. They were not interested in changing the laws which sought to separate them. They wanted only to make music and to dance...together. Clegg's white middle class background differed greatly from that of Mchunu, a Zulu migrant worker who came to Johannesburg in search of employment. The two found their common ground musically and began performing together. They launched their groundbreaking group Juluka in 1979 with the debut album Universal Men.

In an interview conducted during this summer's reunion tour, Clegg recalled the difficulty the duo had in assembling and then keeping a group together. "Juluka was Sipho and me," he said. "Our band members changed all the time. We went through, like, eight drummers and five bass players. They couldn't understand what it was we were trying to do." Juluka's problem was twofold. "We had an outward battle with the media, with the radio, with the TV, with the government. There was an inward battle with the band members." For Clegg and Mchunu, mixing musical cultures seemed perfectly logical. "We had very strong ideas about what we wanted to do."

After two platinum and five gold albums, Juluka fell victim to the pressures of international success and Mchunu returned to a traditional life on his family's farm in Zululand. Political, business, and management demands had taken their toll. Around this time, Juluka's musical balance had begun to tip in favor of rock, and so, remembered Clegg, "...he (Mchunu) basically thought, the stuff that's going down internationally is not really the traditional stuff...It's not the stuff that's being put on the radio because it's in Zulu. So it's always going to ride second best to the mainstream of what Juluka was doing." In addition, other responsibilities weighed heavily on Mchunu. "You know," continued Clegg, "He has 29 kids and five wives. He didn't want to tour anymore internationally, and so the band broke up."

Mchunu became involved in development projects in his community and built a school with profits from Juluka. He also tried starting his own traditional band. Nama Bhubesi released two albums and toured South Africa, but the timing was wrong. "Traditional music in the late 80s was seen to be backward," explained Clegg, "(It) was seen to be politically retrogressive, reactionary. And the rise of Inkatha meant that traditional Zulu music was seen as aligned to tribalism. There's a very strong tension in South Africa between modernism and tribalism." The group disbanded.

Clegg's musical path after Juluka is well known. He continued on, launching his new group Savuka in 1986, just one month before South Africa declared a national state of emergency. Amid the climate of violence and censorship, Clegg wrote some of his most politically powerful work. Songs like "Asimbonanga" (a tribute to then-jailed Nelson Mandela, the song was banned from South African radio), "Human Rainbow," and "One Human One Vote" captured the mood of a desperate nation. Tragedy struck Clegg and the group as friends, colleagues, even band member Dudu Zulu, were killed in the dark years of apartheid.

Savuka is a Zulu term meaning "we have risen" or "we have awakened." Does Clegg feel he's accomplished that? "Yeah, we've done that," he said, proclaiming the end of the group. "The Savuka project is over." His focus now is set clearly on the future.

After concluding the summer tour, work will resume on a new studio album with Juluka to be completed early in 1997. Clegg is also involved in several other endeavors, including two South African radio stations, a concert promotions company, and MTV South Africa. His concern with promoting the music of his country goes well beyond making records. "I have a very broad interest in extending my musical experience into these areas which affect music," he said, referring to the business activities. "I think that music in South Africa has had a bad deal for a long time."

Two years ago Clegg started his own record company, Look South, in which Juluka will play a major role. "I'm hoping for Juluka to be the flagship of the record company. After which we'd like to sign just three acts; a traditional act, a dance act, and a rock act. Basically as the three major modes of music now current in South Africa." Despite his wish to "keep it small," Look South (along with the other music business opportunities) places Clegg in a unique situation. He has both the position and the ability to affect the course of popular music in South Africa.

And what of Juluka? The group conducted a 27 city summer tour of the U.S. and Canada in support of the compilation CD Putumayo Presents: A Johnny Clegg and Juluka Collection [Putumayo World Music]. It's quite different from 1991's The Best Of Juluka [Rhythm Safari]. None of the songs are duplicated and, according to Clegg, "We think the songs on the album are a very good reflection of the best of our songwriting."

The concert crowds were enthusiastic and populated with longtime fans as well as curious newcomers. The show typically opened with the band performing "Cruel Crazy Beautiful World" and a number of other well known Savuka favorites. During the song "Siyayilanda," each band member was featured with an extended solo before departing. Clegg remained on stage taking a few minutes to talk about and then introduce Sipho Mchunu. The audience reacted with shouts of "Welcome back, Sipho!"

Clegg and Mchunu began with "Thula 'Mtanami" (from the album Universal Men). Mchunu sang lead while Clegg took the unusual, but seemingly comfortable, supporting role. One by one the rest of the group reemerged to take their places on stage. Juluka had returned.

According to Clegg, each Juluka album was a different musical experiment. He expressed the group's desire to experiment even further. "The stuff that we're playing now is like, hiphop with Zulu guitar...Euro-dance rhythms, reggae, and Zulu guitar and concertina. It's very modern," he asserted, shrugging off concerns about offending old listeners. Clegg himself has been funding the studio project and appears content to "give the Juluka direction of songwriting a chance to breathe and develop and see how that works. We're both (himself and Mchunu) very relaxed about this. There's no pressure or urgency."

With a new album in the wings and so many other projects on his plate, Clegg is optimistic about the future. "Our coming together is in a way (a) very important reaffirmation that you can continue in the new South Africa as a culturally based group mixing music and mixing ideas."

While the new South Africa struggles to redefine itself, Clegg and Juluka continue to explore new possibilities of their own. The future for all South Africans is certain to be a challenge but, as Clegg himself wrote, "Gotta keep looking at the skyline, not at the hole in the road" (from "Your Time Will Come" [Heat, Dust & Dreams]).

Universal Men, the celebrated debut Juluka album, turns 21 this month. Richard Pithouse reports on an album that, despite being largely ignored at the time of its release, launched an inspirational career and become a national treasure.

Copyright Richard Pithouse

October 25 2000

Reprinted with permission of Mr Pithouse

http://www.talkingleaves.com/pithouse.html

http://www.nu.ac.za/ccs/default.asp?10,24,10,15

In the mid 70's Johnny Clegg and Sipho Mchunu started playing together as a duo under the name of Johnny and Sipho. Their infectious melodies and gentle presence didn't disguise the fact that this union between an illiterate gardener from rural Zululand and a Jo'burg academic was as radical a musical statement as it was possible to make at the height of apartheid repression. But Johnny and Sipho were a lot more than just Verwoed's worst nightmare. From the earliest days their music was infused with a remarkably perceptive engagement with their time and place that made it as timeless and universal as anything by Marley or Dylan.

Sipho Gumede, who was laying down bass grooves for the out-there jazz band Spirits Rejoice at the time, remembers that: "I saw Johnny and Sipho playing as a duo at the Market Cafe and I was excited by what I saw. It was the first time I'd seen a white guy playing African music and the music was very strong. We got talking and they invited us to join the recording project."

So Johnny and Sipho went into the studio with the country's best musicians - people of the calibre of Sipho Gumede; Mervyn Africa, who went on to play with Jazz Africa in London; Colin Pratley from the legendary Freedom's Children, who now runs a home for AIDS babies in Durban and Robbie Jansen, who, of course, remains the inimitable Robbie Jansen.

Their producer, Hilton Rosenthal, had a simple plan: "to avoid commercial pressures and to give the musicians a mandate to experiment and be spontaneous. I thought we'd just put them in a room and see what came out." And the gamble paid off, spectacularly. Johnny Clegg remembers that "The most incredible aspect of the recording process was that the jazz musicians from Spirits Rejoice managed to sound completely different to their normal sound. The whole project was, musically, completely new. No one had done this before - we were flying a kite and hoping to be struck by lightning."

21 years on Sipho Gumede enthuses that "Universal Men still sounds fresh. It's one of those albums that will be there for life. It was an innocent album. We went into the studio with the aim of making great music. No one was thinking about how many units we would sell. We just thought about the music." Hilton Rosenthal speaks for many when he says that "There've been other great moments - like Asimbonanga and Scatterlings - but Universal Men is my favourite album. I have a hard time thinking about Universal Men without the hair on my neck standing up."

The band believed, firmly, that they had produced something important but everyone in the industry told Rosenthal that it was "too black for whites and too white for blacks." No radio station under the jurisdiction of the apartheid state would play the album so Rosenthal took it to Capital Radio in the Transkei, who played the single, Africa, to an enthusiastic but tiny listenership and to Radio Swazi where Mesh Maphetla burst in to tears when he heard Africa.

The album duly hit the streets late in October 1979. The sleeve carried a picture of a two men - one white and the other black. They were dressed in paisley waistcoats, beads and car tyre sandals. But they weren't hippies. Sipho Mchunu looked into the camera with all the resoluteness of a revolutionary Johnny Clegg gazed into the distance with a questioning intensity.

The name of the band appeared as an engraving on a gold bar. It's shimmering glitz clashed, pointedly, with the more organic colours of the sky, the rocks, the men and their clothes. Juluka means sweat in Zulu and the message couldn't have been clearer: Johannesburg's wealth and glamour is built not just on gold but also on the sweat of the men, the migrant labourers, who mined that gold. But Universal Men was a world away from the abstract sterility of Marxist dogma. On the contrary it was more like the words of an African Pablo Neruda had been set to the most sublime music - a very human response to an inhuman society.

Johnny Clegg explains that "Universal Men is about bridging two worlds. Going and coming. While the worker is on route, on a bus or a train, he is given the time to look over the distances, geographic and otherwise, in his life. Migrant labourers, in Africa, Europe, everywhere, are like universal joints. They are this incredible human resource who are just sucked up by the capitalist system and used anywhere. The system makes no concessions and so the workers have to create a whole new universe of meaning."

The album is a largely acoustic mixture of Anglophone and rural Zulu folk. Clegg's lyrics have an extraordinary rhythm, depth and emotive power and are, at times, a little otherworldly or perhaps old fashioned. Clegg explains that "There was so much hardness in the migrant life and yet I experienced incredibly human moments with my buddies. They lived such a rich and full life with a highly developed sense of humour and understanding of human nature. For me there was something magical and mystical in this bleak life and I felt that I needed another language to capture it and to humanize the suffering ."

The album opens with Sky People. The title refers directly to the amaZulu - the people of the sky (iZulu). One man's story rolls, like a wave on the ocean, across the larger story of his people - their past and their hopes for the future. He asks

Where did the time, time, time go ?

My old eyes can hardly see the green fields leaving me behind

I worked the earth and turned the blade with a strong heart and steady hand

Seasons wheeled across the sky

I turned around and found that I was old

Trembling heart body cold

Wind and rain take their toll

The album was recorded just months before Zimbabwe won independence and Clegg remembers that "there was a huge fight in the studio. "I wanted to use the line 'The drums of Zimbabwe speak/They roll across the great divide' but everyone was convinced that would lead to the album being banned so we eventually changed it to 'The drums of Zambezi speak' " But the next lines remained: 'Smiling spear with teeth of white/Give me strength to face the night/Ancient Song Bless My Life/See me through to see the morning light.' This was a world away from the 'happy native' crap of IpiTombi.

Many of the themes in Sky People were developed further on later albums and this is also true of the second track, Universal Men. Clegg explains that the title track is the pivot on which the whole album turns. It pays respect to the workers with whose sweat prosperity was built:

From their hands leap the buildings

From their shoulders bridges fall

And they stand astride the mountains and they pull out all the gold

The songs of their fathers raise strange cities to the sky

And the chorus is a meditation on separation and home coming.

I have undone this distance so many time before

That it seems as if this life of mine is trapped between two shores

As the little ones grow older on the station platform

I shall undo this distance just once more

My brother and my sisters have been scattered in the wind

Dressed in cheap horizons which have never quite fitted

And for centuries they've traveled on that pale phantom ship

Sailing for that shore which has no other shore

For a while the vision seems bleak.

The rivers of their homelands murmur in their dreams

They're shackled to that distance till heaven lets them in

But then Clegg finds a way to defend hope.

Well they could not read

and they could not write

and they could not spell their names

But they took this world in both hands and they changed it all the same

And from whence they came and where they went nobody knows or cares

Cast adrift between two worlds they could still be heard to sing

The third song, Thula 'Mtanami (Hush My Child), has all the evocative power of an archetypal lullaby. It is beautifully sung by Sipho Mchunu and was included on the album because, according to Clegg, "Sipho knew that his wife would be singing it to their child back home." One can't help but wonder if migrant workers don't also sing lullabies to parts of themselves.

The fourth track, Deliwe, was overlooked for years but it was taken to a large new audience when it featured on the carefully put together Putumayo compilation, A Johnny Clegg and Juluka Collection. It has recently been worked into the Juluka set list and many now rate it as their favourite Juluka song. It's the only song on the album which doesn't deal directly with the migrant labourer experience but it is part of the broader theme of movement and separation in that its about a person, Deliwe, deciding whether or not to leave South Africa. It warns that not all waters wash us on the inside and that, in a foreign land, Deliwe will be haunted by the melodies of Africa and, eventually, judged by the north winds (a metaphor for the winds of change sweeping down from the north).The song 's simple prayer has haunted more than a few expatriate South Africans and persuaded just as many to return home and live in hope:

Oh, Bless this water

Bless this land

Give us food to eat

Let our herds span the hills

Let them graze in peace

If soldiers march across our fields give them eyes to see

The children singing in the sand

Songs in the north wind

The next song, Unkosibomvu (The Red King), begins with a sound that is somewhere between Malombo and Amampondo, and develops a slightly ominous tone - as though there's danger beneath the surface. Clegg explains that it deals with the martial psyche which is able to generate enormous power but also has a dark side. The Red King refers to "a romantic iconography of a mythological bloody king whose ability to force his will on others is admired."

Africa, which was Capital Radio's first ever number No. 1, remains a live favourite. Its sing along chorus, means, in translation, "in Africa the innocent are always crying." Clegg describes it as a cryptic song which refers to the strong rural belief that good is limited while evil is pervasive and so the good suffer while the bad prosper.

Uthando Luphelile (Love has Gone), the 7th track, has a much harder edge than anything else on the album and, musically, it anticipates the Juluka inspired African rock movement of the late 80's led by the likes of Via Afrika and éVoid. The lyrics have a tight, edgy, urban feel. Clegg describes it as "a very weird song" and explains that "I was trying to look at the problem of prostitution at the migrant hostels - at the power of the slick city girls and to make the point that bourgeois men are also trapped by the same illusions about fantasy women." The songs warns that once you've "seen her in the disco club busting out all over" she "infiltrates your desire and makes you open wide/ She walks down the convolutions of your cerebellum/And tickles the right hemisphere with an electric tongue...You will persround her like a fly" but "you will never get to hold that woman because she's a phantom in your mind."

The profoundly moving Old Eyes is about homecoming. Clegg explains that, for the migrant labourer "home coming is everything - you're carrying presents and it's the moment when you reveal yourself to your community as a successful person. You become a source of abundance; it's an elevated and life giving moment in the migrant universe. There is redemption. All the degradation and alienation which you've endured is redeemed and transformed into a hugely meaningful event when you arrive home.

But in this song, the longed for redemption is out of reach - shattered between the anvil and hammer of apartheid. The returning worker finds that he is the "only one to witness my homecoming" and reflects that:

When I left that mountain land so gold and green

I was a sturdy 16 years

The work was hard and the wage was low

And the seasons past me by one by one

And I dreamed Maria you would wait for my return

We'd build a home upon the rock beneath the smiling sun

He finds an old man who remembers from his youth who tells him that:

Son I'll be old until I die now

And then I will join our people in the sky

I am not the one to ask why our people have been scatted in the wind

Yyou've got old eyes - amehlo madala - you've seen much too much for one so

young

The album ends with Inkunzi Ayihlabi Ngokumisa which is a reworking of an ancient war song sung by Mchunu and adapted to the evocative sounds of the Clegg's mouthbow. The title refers to a traditional idiomatic expression which means, in translation, "A bull doesn't stab by means of the way in which its horns have grown." It's an exceptionally beautiful piece of music and their gentle, meditative interpretation speaks of a softness - an openness to new ways of being. It was an inspired way to end the album.

There is a long list of South African artists who have made great albums. It includes, amongst many others, the likes of Philip Tabane, Winston Mankunku, the Malopoets, Bright Blue, Sakhile, Jennifer Ferguson, the Gereformede Blues Band, Plum and Prophets of Da City. But there's always something a little tragic about a great album, like Bright Blue's The Rising Tide, that's not followed up adequately or at all. The list of artists who have developed a substantial body of superb work is small and doesn't extend much beyond the likes of Abdullah Ibrahim, Tananas, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Hugh Masakela, Miriam Makeba and Johnny Clegg.

Part of the magic of Universal Men is that it was the start of an incredible career for Juluka. Two years after its release they put out African Litany with the irresistible Thandiwe, the massive cross over hit and enduring cult classic Impi and the lyrical African Sky Blue which goes, in part,

The warrior's now a worker

And his war is Underground

With Cordite in the darkness

He milks the bleeding veins of gold

When the smoking rockface murmurs he always things of you

African Sky Blue

Will you see me through?

Radio stations on both sides of apartheid's colour line had to give in to a ground swell of popular demand and Impi became a massive hit and broke the album nationally. Hilton Rosenthal remembers, rather ruefully, that "suddenly Universal Men was the great first album." It had only sold 4000 copies when it was first released but it now went gold.

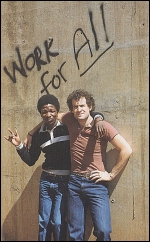

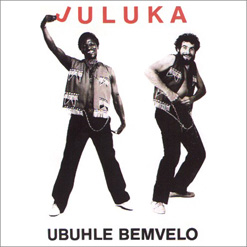

The following year Juluka released Ubuhle Bemvelo which included reworkings of some of the favourite songs from the Johnny and Sipho days including the infectious Woza Friday and Umfazi Omdlala. In the same year they released Scatterlings, an album which had a harder edge, musically and politically, than anything they'd done before. The justly famous title track charted in the UK at the time and, when it was rerecorded with Savuka, went to No.1 across Europe. The album was packed with superb songs which included Siyayilanda, dedicated to murdered trade unionist Niel Aggett, as well as Simple Things and Spirit is the Journey. It's the most spiritual of all the Juluka albums but it never goes anywhere near sentimentality. It's more Heidegger than Oprah. In 1983 Scatterlings was followed up by Work for All an album which, again, was harder and more militant than anything they'd done before. The first track, December African Rain, remains a sing along live favourite and Gunship Ghetto and Mdatsane (Mud Coloured Dusty Blood) engaged, directly, with the violence of oppression and resistance. And of course the title track is as relevant today as it was 17 years ago:

Hear them sing in the streets now

Hear the sound of marching feet now

Sifun'umsebenzi - work for all - we need to work to be

Sifun'umsebenzi - work for all - there's a joblesss army in the streets

Sifun'umsebenzi - work for all - in a wage a hidden war

Sifun'umsebenzi - work for all - there's a jobless army at my door

Sifun'umsebenzi - funumsebenzi

Work for All was followed, in 1984, with Musa Ukungilandela, an all Zulu album with a tight, hard, urban feel. The big hit was Ibhola Lethu, written for the Mainstay Cup. Later that year they released a mini-album of tracks especially recorded for the European and American markets. Each of their increasingly militant 7 studio albums is a coherent and powerful statement and there's not a single song that doesn't make for a captivating listening experience today. It was a remarkable achievement.

In 1985 Mchunu left the band and recorded, amaBubhesi a solid but overlooked maskanda album in the shameni style while Clegg returned as a solo artist with Third World Child. It's heavy reliance on synthesizers makes it sound very 80's today but it was a taught and powerful response to the dark days of the state of emergency which, somehow, managed to hold on to hope in the midst of barbarism. Clegg then formed Savuka and released and EP and four albums all of which made direct political statements. Crazy Beautiful World began with a song One (Hu)Man One Vote the first words of which were, translated from the Zulu, "The young boys are coming, the young boys are coming, They carry homemade weapons and a bazooka. They say 'We have agreed to enter a place that has never been entered before by our parents or our ancestors and they cry for us, for we do not have the right to vote.' " With the exception of the incandescent Heat, Dust and Dreams none of the Savuka albums was as portent an artistic statement as any of the Juluka albums. The lyrics were always well crafted, intelligent and important and there were fragments of transcendent insight. But the records tended to sound like collections of songs rather than albums and their engagement with the pop sounds of the time give them a slightly ephemeral feel. The Savuka period did produce one astonishingly good song though - Asimbonanga: a soaring tribute to the then imprisoned Nelson Mandela. It was on the first ever Savuka release, a 4 track ep, and is clearly up there with Mannenberg and Weeping as one of the greatest South African songs ever.

But the poppier Savuka material did win major international success which, in turn, won the band, their vision of transcendence and their back catalogue, major respect in white South Africa. In a Durban they suddenly went from playing to 3000 people in the University Hall to playing for 25 000 people, and a few extras who'd scaled the walls, at the Village Green. When Europe said that it was cool to be into Johnny Clegg he suddenly became a national icon and was able to reach out to many more people. Such are the sad ironies of colonial culture.

Juluka reformed in the late 90's and released the forgettable Ya Vuka Inkunzi in 1997 which was later rereleased as Crocodile Love. They are set to release another album shortly and they remain, through their live performances, a vital force in South African culture. Clegg and Mchunu are still passionate people and they may well make great music again. Perhaps, as with Bruce Springsteen's Ghost of Tom Joad, they may reinvent themselves by returning to their acoustic roots and record another album with the gentle potency of Universal Men.

The world has changed in the last 21 years but lives are still being shattered by the machinations of inhuman powers. A new vision of hope and humanity from Juluka would be rain in the desert.

*Sipho Mchunu was not available to be interviewed for this article as he was on holiday in Paris

http://www.freemuse.org/04artist/johnny01.html

|

JOHNNY CLEGG |

•

RealAudio sound file:

•

RealAudio sound file:

![]()

"Censorship is based

on fear. It is conservative and wants to preserve a particular set of values,"

says Johnny Clegg who discusses censorship in a larger context:

"Censorship is a brute blind reaction to a brute blind recognition that

information is not neutral..."

Sound file duration: 5:50 minutes.

Hi

| Low (Interviewed

in South Africa in 1998 by Mr. Ole Reitov)

National Public Radio – The W orld Café, Musician’s Day, 18 June

1993

06-18-93 interview.pdf

JC as guest DJ, World Cafe, 18 June 1993

by Chris Heim Chicago Tribune, April 19, 1991 http://www.talkingleaves.com/articles/rosenthal.html

Hilton Rosenthal (Johnny Clegg's ex-manager) and Sipho Mchunu Zululand, Christmas 1987

Rosenthal on the connectivity of music: "...it doesn`t matter where music comes from. It`s something that can touch the heart no matter where it emanates from."

"I had a call from the president of Warner Bros. (Records)," South African record producer Hilton Rosenthal says. "And he said, 'Paul Simon`s found this song that`s on a cassette someone gave him. We know the cassette`s called Gumboots. We don`t know any of the song titles Can you find out more about it?'

"At that stage, I don`t think either of us dreamed that this was Graceland. It was just, 'Let`s do some music and see what happens.' The rest is history, I guess."

It is, in fact, some of the more significant pop music history of recent times. Paul Simon`s Graceland album almost single-handedly introduced South African mbaqanga music to the U.S. and played a major role in drawing attention to the phenomenon of world music.

Other things helped. Johnny Clegg, leader of the interracial South African pop-mbaqanga bands Juluka and Savuka, broke through internationally, selling millions of albums around the world. Harry Belafonte recorded Paradise in Gazankulu, an album of South African influenced-music done with South African musicians. Some of the originators of South African mbaqanga Mahlathini, the Mahotella Queens and the Makgona Tshole Band reunited for the first time in years and became international favorites.

Working behind the scenes in every case was Rosenthal, the crucial catalyst for world music. Now he hopes to take his vision a step further with the start of his own American-based label, Rhythm Safari Records.

Rosenthal grew up in white, middle-class surroundings in segregated South Africa. He liked the Beatles and the Rolling Stones but never listened to black South African music. He played in a band but had no plans to make a career in music.

"I`d worked for my father`s firm, they were auditors and got bored out of my skull in the first few days. A couple of days later, my agent called and said, 'I`ve got this gig for you playing on a boat going to Madagascar, the Seychelles, this whole Indian Ocean cruise.' And I said, 'Well, that`s the end of my accounting career.'"

After college, Rosenthal went to work for the Gramophone Record Co., the South African affiliate of CBS Records. About a year later he was put in charge of the black music division. South African music then was strictly segregated by race.

This didn`t make sense to Rosenthal, who, in 1978, persuaded CBS International to give him a small budget for musical experiments. He began working with Clegg and black musician Sipho Mchunu, who were performing traditional acoustic Zulu music together. He encouraged them to work with a band (that became Juluka), add some electronics and English, and combine Zulu music with Western pop.

"When we made the first Juluka record, people looked at us as if we were nuts, "Rosenthal says. "The comments from the record company, from everyone were, 'This is too black for whites and too white for blacks.'"

Rosenthal went on to create (and eventually sell) Music Inc., one of the largest independent record companies in South Africa; produce every album Clegg did with Juluka and his current band, Savuka; and assist Simon and produce Belafonte. In 1987 he relocated to America, and at the start of 1991 he launched Rhythm Safari Records.

The label debuted with four titles. Like his past productions, they offer a highly accessible merger of pop and ethnic music presented with crisp, modern production values. The music is glossy and filled with catchy hooks, yet still connected to the traditions from which it springs.

The Best of World Music is a sampler of pop-worldbeat hits of recent years. The Best of Juluka highlights material (over half previously unreleased in America) from that groundbreaking South African band led by Clegg and Mchunu. LAtino LAtino: Music from the Streets of L.A showcases what Rosenthal says is a largely neglected but exciting salsa and Latin jazz scene in Los Angeles. The fourth release is An African Tapestry, worldbeat influenced New Age/light fusion from classical guitarist David Hewitt backed by a group of South African musicians.

"I thought personally the four releases represented pretty clearly most of what I`m going to be doing," says Rosenthal. "It`s very difficult to define (what connects all these artists), but I know there`s a common thread there. That`s one of the things I really want to put across with the label. That it doesn`t matter where music comes from. It`s something that can touch the heart no matter where it emanates from."

Hilton

Rosenthal

Hilton

Rosenthalartists (H) - http://reggae.discogs.com/artist/Hilton+Rosenthal

Profile:Accountant, musician, producer, and businessman Hilton

Rosenthal grew up in typical white, middle-class surroundings of a segregated

South Africa. He liked the Beatles and the Rolling Stones but had never listened

to black South African music. An accountant with his father's firm, he played in

a band but had no plans to make a career in music.

After college though, Rosenthal went to work for the Gramophone Record Co.,

the South African affiliate of CBS Records. About a year later he was put in

charge of the black music division (music then was strictly segregated by race).

Despite this, in 1978 he persuaded CBS International to give him a small budget

for musical experiments, and he began working with

Johnny

Clegg and Sipho Mchunu who were performing traditional acoustic

Zulu music together. He encouraged them to work with a band (that eventually

became Juluka),

add some electronics and English, and combine Zulu music with Western pop -

although the music was initially considered "too black for whites and too white

for blacks". Subsequently, he produced every Juluka and Savuka

album.

Rosenthal then went on to form (and eventually sell to EMI before his 1985 move

to the USA) Music Inc., one of the largest independent record companies

in South Africa.

In 1990 he launched Rhythm Safari Records, with

Rhythm Safari (Australia) following in 1997.

Rhythm Safari was

formed in Los Angeles in 1990 by veteran music producer/executive, Hilton

Rosenthal, with the aim of bringing a variety of quality music to the

marketplace. The label initially concentrated on world music, but later

developed to have success with releases by Carole King, Foreigner, Christopher

Cross and Boyz Of Paradize.

The Australian label was formed in 1997 and is distributed by Universal Music

Australia & New Zealand.

courtesy of Rhythm Safari +

http://www.amo.org.au/label.asp?id=208

Rhythm Safari was formed in Los Angeles in 1990 by veteran music producer/executive, Hilton Rosenthal, with the aim of bringing a variety of quality music to the marketplace. The label initially concentrated on world music, but later developed to have success with releases by Carole King, Foreigner, Christopher Cross and Boyz Of Paradize.

The Australian label was formed in 1997 and is distributed by Universal Music Australia & New Zealand.

Hilton's credits include: Producer of all Johnny Clegg (Juluka & Savuka) albums from 1979 - 1993. Other productions include Teddy Pendergrass, Tone Loc, The Horse Flies, Harry Belafonte, Raffi, and music for the films "Power Of One" & ‘FernGully’. Hilton also helped conceive & coordinate the recordings for Paul Simon's Grammy Award winning ‘Graceland’ album .

In the late 1970's Hilton was General Manager of Gramophone Record Company - CBS' joint venture in South Africa. Later he formed Music Incorporated, which became one of the largest independent record labels in South Africa. The company was sold to EMI in 1985 before Hilton's move to the USA.

More recently, Hilton was co-founder and executive of Global Music One/Yourmobile.com, an LA based mobile entertainment company that was acquired by Vivendi Universal's VU Net at the beginning of 2002 and renamed Moviso. Moviso has since been acquired by InfoSpace to become the nucleus of InfoSpace Mobile. http://www.rhythmsafari.com/MintDigital.NET/RhythmSafari.aspx?XmlNode=/About+Us

Johnny

Clegg

Johnny

Clegg artists (J) - http://reggae.discogs.com/artist/Johnny+Clegg n

Profile:

Profile:

"Songwriter, dancer, guitarist and vocalist - in that order."

Johnny Clegg was born on 7th June 1953 in Rochedale, Lancashire, England

and raised in Israel, Zambia, South Africa, and Rhodesia before finally settling

in Johannesburg in 1965.

Young Johnny, who had been learning to play Spanish guitar, was 14 when he met a

Zulu gardener, Charlie Mzila, playing street music near Clegg’s home. For two

years he learned the fundamentals of Zulu culture and traditional "inhlangwini"

dancing as he accompanied Mzila to the migrant labour haunts - from hostels to

rooftop shebeens. It was the height of apartheid, and Johnny Clegg’s involvement

with black musicians and his love for the music often led to him being arrested

for trespassing on government property and contravening the Group Areas Act.

Johnny Clegg’s fast-growing reputation finally reached the ears of Sipho

Mchunu (born 1951), a migrant Zulu worker who had come to Johannesburg

looking for work. Intrigued, Mchunu tracked Johnny down and challenged him to a

guitar playing competition, sparking off a friendship and musical partnership

that helped transform the face of South African music. That was 1969.

After Clegg completed his education, graduating with a BA (Hons) in Social

Anthropology and Political Science from the University of the Witwatersrand in

Johannesburg, he spent four years as a lecturer.

Their

musical breakthrough came in 1976 when, as "Johnny and Sipho", they

secured a major recording deal and produced their first hit, "Woza Albert".

Under the guide of producer

Hilton Rosenthal, the band

Juluka was

formed around these two core members. However, because their music was in total

contravention of the cultural segregation laws of the time, it was subjected to

censorship and banning, and their only way to access an audience was through

touring. In late 1979 their first album, "Universal Men", was released.

It received no airplay but became a word-of-mouth hit. They were able to tour in

Europe and had two platinum and five gold albums, becoming an international

success. Juluka was finally disbanded in 1985 as Mchunu returned to his roots in

Zululand to become a livestock farmer.

Their

musical breakthrough came in 1976 when, as "Johnny and Sipho", they

secured a major recording deal and produced their first hit, "Woza Albert".

Under the guide of producer

Hilton Rosenthal, the band

Juluka was

formed around these two core members. However, because their music was in total

contravention of the cultural segregation laws of the time, it was subjected to

censorship and banning, and their only way to access an audience was through

touring. In late 1979 their first album, "Universal Men", was released.

It received no airplay but became a word-of-mouth hit. They were able to tour in

Europe and had two platinum and five gold albums, becoming an international

success. Juluka was finally disbanded in 1985 as Mchunu returned to his roots in

Zululand to become a livestock farmer.

Later that year, Johnny Clegg released his first solo album "Third World

Child".

He also forms

Savuka, another inter-racial crossover band in 1986, blending African

music with European (especially Celtic) influences. One EP and four albums were

released between 1986 and 1993 before that band was terminated.

Since then, Johnny has recorded solo (briefly reforming Juluka for one

album and a tour), including his latest studio album "New World Survivor"

in 2002 and continues to perform live with resounding success, including his

support of Nelson Mandela’s "46664 AIDS Awareness Concerts" in South Africa and

Norway during 2004 and 2005.

In France he is affectionately known as "le Zoulou blanc", the white Zulu.

Juluka

Julukaartists (J) - http://reggae.discogs.com/artist/Juluka

Profile:

Johnny Clegg (who went to six different schools in three different countries in five years and was learning to play classical Spanish guitar) was 14 years old when he heard a garden boy by the name of Charlie Mzila play guitar at a corner cafe in Yeoville, Johannesburg. The sound of the Bellini guitar intruiged little Johnny, and over the next few years he learnt fundamentals of the Zulu culture and traditional "inhlangwini" dancing and stick fighting as he accompanied Mzila to the migrant labour haunts. Their

first musical breakthrough came in 1976 when, as "Johnny and Sipho", they

secured a major recording deal and produced their first hit, "Woza Albert".

Under the guide of producer

Hilton Rosenthal, the band Juluka (meaning "sweat that comes from

dancing" in Zulu and named after Sipho's head bull!) was formed around these two

core members.

Their

first musical breakthrough came in 1976 when, as "Johnny and Sipho", they

secured a major recording deal and produced their first hit, "Woza Albert".

Under the guide of producer

Hilton Rosenthal, the band Juluka (meaning "sweat that comes from

dancing" in Zulu and named after Sipho's head bull!) was formed around these two

core members.

http://inmyafricandream.free.fr/

Members: Johnny Clegg & Savuka

Johnny Clegg & Savukaartists (J) - http://www.discogs.com/artist/Johnny+Clegg+%26+Savuka

Profile:

Savuka

(based on the Zulu word for the phrase "we have arisen") was formed by

Johnny

Clegg in 1986 after the demise of his musical partnership with Sipho Mchunu

as Juluka.

Savuka

(based on the Zulu word for the phrase "we have arisen") was formed by

Johnny

Clegg in 1986 after the demise of his musical partnership with Sipho Mchunu

as Juluka.

Whereas Juluka were more of a local cultural curiosity and crossover project

during the height of apartheid and the pair’s musical relationship was often

subjected to racial abuse, threats of violence and police harassment, Savuka

went one bold step further: multi-racial, of course, but they also had a

political agenda. The issue of racial and social injustice, which has been at

the core of so much of Johnny Clegg’s work over the years, was more prominent.

Says Clegg: "Savuka was launched in the State of Emergency, 1986. The entire

album was hard-hitting, it was directly political and it had very strong

political metaphors. That’s the album I wrote the song for Mandela and released

it commercially inside South Africa, that’s the album which was also restricted

and banned, the video was heavily banned."

"Musically, Savuka tended to be more of an international melange, it was more

rock, it was more hard, it was a harder edge sound and we were not drawing just

on Zulu guitar. I drew on many other influences. I drew on Zimbabwean guitar

music, I drew on Zairian music, I drew on Latin-American rhythms and even in the

last album I drew on a traditional Hindu prayer song."

The breakthrough album was "Third World Child" in 1987 but their success

reached its zenith with "Cruel, Crazy Beautiful World" (1989) which was

followed by "Heat, Dust & Dreams" (nominated for a Grammy) in 1993.

Also in 1993, percussionist Dudu "Zulu" Ndlovu was assassinated in a conspiracy

relating to a taxi war, and Savuka was terminated that same year.

Johnny Clegg - Lead vocals, Guitars, Concertina, Mouth Bow, Jaw Harp

Steve Mavuso - Keyboards, Backing Vocals

Derek de Beer - Drums, Percussion, Backing Vocals

Keith Hutchinson - Keyboards, Saxophone, Flute, Backing Vocals.

Dudu "Zulu" Ndlovu - Live Percussion and Dancing, Backing Vocals.

Solly Letwaba - Bass Guitar, Backing Vocals.

Mandisa Dlanga - Additional Backing Vocals.

URLs:

http://inmyafricandream.free.fr/Members:

Johnny Clegg This

South African documentary takes a look at the traditional Nguni cattle and the

people who care for them. Focusing mainly on the Zulu nation, we look at an

assortment of people and how their lives are related to and influenced by their

cattle.

This

South African documentary takes a look at the traditional Nguni cattle and the

people who care for them. Focusing mainly on the Zulu nation, we look at an

assortment of people and how their lives are related to and influenced by their

cattle. 75 minutes, Parental Guidance

Documentary, Drama, On the art circuit

July 28, 2006

http://www.tonight.co.za/index.php?fArticleId=3360481&fSectionId=358&fSetId=251

Director: James Hersov

Cast: Mkombiseni Majola, Ningi Mahlaba, Sipho Mchunu, Sibuyisile Sibiya, Pitika

Ntuli (narrator)

Running time: 75 minutes

Classification: PG

With Heaven's Herds, documentary maker James Hersov has focused on the

obsessive, intimate and often quirky relationship forged over hundreds of years

between the Nguni people and their indigenous Nguni cattle.

It is narrated by Professor Pitika Ntuli who weaves in his own personal story

with that of the Nguni breed, and introduces the viewer to a cast of Zulu

characters at specific points in their lives which, traditionally, incorporate

the cattle.

Colonial prejudice over the past hundreds of years in South Africa robbed the

indigenous people not only of their traditions but also their cattle.

After the Zulu War, the British slaughtered thousands of cattle and confiscated

the royal herd as a way of saying "what is important to you is inferior to us",

which struck at the very heart of the Zulu nation.

The authorities regarded Nguni cattle as worthless, scrub cattle and during

apartheid people were forbidden to breed them

The pure Nguni strain almost became extinct but a small group of breeders

kept them going and now they are finally being recognised for their hardiness,

adaptability, economic and heritage value.

The filmmaker didn't concentrate on KwaZulu-Natal only, since there are pockets

of Nguni cattle found all over the country.

The film is actually strongly character-driven, despite the topic being animals.

It follows individuals who are either undergoing specific rituals which

incorporate the cattle in some way, or whose lives are intimately bound up with

the cattle.

Such as cattle-whisperer Mkombiseni Majola, who refuses to slaughter his cattle

because they are like family to him and, when he dies, wishes to be wrapped in

the hide of his Nguni bull.

Or Subuyisile Sibiya who has waited for seven years for her fiancé to raise

enough money to buy the 11 cattle needed for her lobola (bride wealth).

Nguni poetry and prose reflects a deep respect for their cattle, which is

evocatively expressed in the praising and naming of cattle. - Synopsis

| Credits | |

|---|---|

| Cast | Mkombiseni Majola, Ningi Mahlaba, Sipho Mchunu, Subuyisile Sibiya, Shiphomandla Zungu. Narrated by Pitika Ntuli. |

| Director | James Hersov, Sofia de Fay |

| Screenplay | James Hersov, Sofia de Fay |

| Music | Sea Grealy |

| Cinematography | Efpe Senekal, Mark Rowlston |

| Editing | Robert Haynes |

| Sound formats | Dolby Digital, Sony Dynamic Digital Sound, DTS |

| Soundtrack | Not available |

| Made in | 2006 |

| Produced by | Flying Fox Productions |

| SA Distributor | Ster-Kinekor |

He's a good man, Dave Ornellas. But then he's always been good; rising like a

colourful prophet of old from the smoking stage, with a voice Joe Cocker might

have envied. Wild black hair and flowing beard, he chose - in the early years -

the complex simplicity of making music the African way.

No, not fusion. But earthy stuff - the virile, extraordinary, substance concept

albums are made of.

Strange to write that now, thirty-something years on.

The "concept album", with its long, interwoven tracks, telling a musical story,

was the avant-garde pop symphony of the 1970s. It is also long dead. Everyone

did concept albums - Pink Floyd with Umma Gumma, Genesis (the original Genesis,

that is, when Phil Collins was a drummer, not a weasel-voiced vocalist) produced

them with Trespass and Foxtrot (and at a push The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway).

Deep Purple went even further, seconding the entire Royal Philharmonic and

Malcolm Arnold in the Royal Albert Hall to do their seminal Concerto for Group

and Orchestra and equally impressive, but not as melodic Gemini Suite. Add Uriah

Heep and Free, who fringed - and Keith Emerson (as the Nice and later with ELP)

who turned classical themes - like Prokofiev's Lieutenant Kije Suite - into

mind-numbing extravaganzas, sometimes stabbing the keyboard with a knife to hold

the note. It was the age of course, resurrecting itself from the post-World War

2 How Much Is That Doggie in the Window? Mocking Bird Hill syndrome; the

hysterical - but musically brilliant - pop culture of The Beatles and the

raunchy y'all R&B of the Rolling Stones. And who can forget The Who?

In Johannesburg, bursting, like Durban, with musicians aeons ahead of their

time, Ornellas added the sunburnt, brown prairies of Africa to the genre of the

concept album - the heady, steady beat of drums, and enough cross-rhythms to

make you dizzy.

Add the mesmerising voices - and the telling story.

Tuck in the ranging flute, the saxophone. The deep bass buzz. And the

mesmerising, talking drums.

African Day, all 17-plus minutes of it, was the birth of a home-grown concept

later taken up by Jon Clegg and Sipho Mchunu, and the other rising sons of South

African music.

"John used to sit at the foot of the stage with 'smoke' from the ice machine

curling down, when we performed," says Ornellas. "He was about 15 years old -

sometimes Sipho was with him. Sometimes they danced."

African Day took up the entire side one of the album of the same name, something

never quite before seen, or heard, in a country alive with indigenous sounds

no-one had worried to emulate, because the "culture" was foreign. In other

words, not "white." And everyone knew, in a society insanely paranoid with

Apartheid-speak, that only "white people" could, well, make music.

The others could develop separately.

Hawk changed - and challenged - that immediately.

In the off stage darkness a voice intoned:

It's dark and still in the chief's village protected by the mountains of the

great southern regions of Africa . . .

Drums echo through the village as the first fingers of light paint the sky with

the fresh colours of morning, and so the days begins . . .

And so, too, the lights came up. It was the prelude to a unique, colourful,

performance, and once caught live, and the story dramatically revealed, was

never forgotten.

It was music theatre on a grand, unique, stage.

One day in the Kraal of Taka,

All the peoples' hearts were filled with fear,

Three men had died and the village waited

For the maddened beast to re-appear.

An African story, this. Of a killer, rogue, elephant, a rampaging, out of

control beast. A story culled from the heat and dust of Africa, a

fast-disappearing natural world around us. An avant garde tone poem.

Ornellas, diminutive now, with craggy face and short, off-black hair, sips

orange juice. We are in the lounge of his Cape Town home, with his young son,

Caleb. His dogs huff and puff in the heat.

At my feet, the instrument of his profession and his success - a guitar. New

strings, in a box, lie on the table.

It is a good meeting.

I last saw him around 1970-71 in Durban. Whatever the year, Hawk headlined at

the Battle of the Bands - an annual bash put on by the music magazine I edited,

Trend, and Durban councillor Peter Breytenbach, who organised the City Hall and

the anti-riot-drug squad. It was a good year for music. On the show were Otis

Waygood Blues Band, Abstract Truth, Scratby Hud, and a collection of good local

bands. Voting was by four judges - I was not one, but my colleague Carl Coleman

was.

Hawk, in full flight tore the house down with a storming set, a beaming

Ornellas, dressed in flowing African-style full-length robes shaking the

perspiration from his oval of deep black hair.

Not bad for a lad who grew up in Cape Town's southern suburbs and went to

Plumstead High School. And learned to play the acoustic guitar.

Ornellas says: "I wanted to go to university, but didn't make it. That was bad

news, because I was pretty keen. Instead, in 1967, I headed north to

Johannesburg and the school of mines. I wanted my future to be in the science of

metallurgy, and eventually landed up on the Kloof gold mine."

It was dismal, and not what Ornellas wanted. But his next move was the nudge

into an entirely new career.

"I went to art school - in the centre of the city. There I met a fellow student

who was very neat on the guitar. His name was Mark Kahn - better known as

'Spook'. He could really play lead, while I tucked myself in on rhythm. Soon we

a pretty tight duo and called ourselves The Buskers and got regular work at that

music hangout, the Troubadour in Johannesburg."

Kahn says: "It was amazing how it all came together. This dude Ornellas could

make things happen. Hey, it was a pretty exciting thing. We kind of rolled up at

these places, you know. Kind of casing the scene. What we really wanted to do

was play with some people - you know, people with drums and keyboard and sax -

that kind of stuff."

Extraordinary things began to slot into place.

Ornellas believes in extraordinary things - like meeting "his hero" for the

first time.

"It was Mike Dickman - he had been playing electric guitar with a group called

Flood which also included Pete Measroch, Rod Clarke and Richard Johnson.Well, I

spent hours listening to Mike, so laid back, so cool, so collected. The man was

a guitar wizard. When he hit the strings, the wood talked."

Richard remembers "Flood was playing a weekly gig at the Troubadour Dave and

Spook would drop by to do a set or two and as most musos do we checked each

other out. In the same block as the Troubadour Keith and Braam were playing in a

group called Toad then as if by fate both bands folded virtually at the same

time; Mike and Pete went on to Abstract Truth and I, together with Keith and

Braam teamed up with Dave and Spook to form Hawk"

Spook says: "This coming together seemed some kind of destiny. Here were these

fellows - just what we were looking for, Dave and I. I suppose we sniffed around

for a while - they could hear what we could do; we could see what they could do.

"They went so far as to let us use their instruments, too.

"We found a togetherness, a synergy. And we found the farm."

Paddock Farm, to be exact. In Morningside, Rivonia, on the outskirts of

Johannesburg.

Says Ornellas: "We had no money; so we grew our own stuff - someone gave us a

huge jar of mayonnaise once, and we ate it for weeks with home grown salads. We

played the Troubadour; we played here and there. We wrote music. We did our own

cover versions. And for a while had a female singer - Maureen England, who made

a name for herself later in folk.

"And we called ourselves Hawk - after a hawk that lived on the farm. We were

beginning to fly, and formulate the direction our music was going to take. We

were listening to a lot of Hugh Tracey tapes - the expert Afro-musicologist who

had travelled Africa placing sounds and music on tape for posterity.

"We went to Swaziland and came back with our own sounds, drums and a burning

desire to make our own brand of African music. From all of this came African

Day."

There is a touch of wistfullness as Ornellas says: "We told a story. It was a

simple one. And we put everything into it - just listen to Keith's sax; the pain

of the elephant is there.

"We produced a spectacle - spears on stage and the like."

It is an understatement of considerable proportions. Hawk's stage spectacular

was a masterpiece of the time - not only on stage, but also in the huge,

open-air concerts that became the rage of the 1970s, rain notwithstanding.

The real miracle was that no-one was electrocuted.

Spook says: "Sometimes I look back - I mean there we were, running around in

leopard skins. Perhaps in hindsight it was just too pretentious. Too much. But

it worked."

Richard says: "Here's something most people have already forgotten - when we

went on stage, we were the first live group to have their own permanent sound

engineers out there among the audience.

"One was Don Williamson, the other Trevor Pitout. We called him Snake - I don't

think anyone ever called him Trevor. Anyway, there they were out there, at their

huge sound desk. Now this was a major technological advance, because we had the

most amazing sound equipment you could imagine.

"So much so that the British group Barclay James Harvest, who were here at the

time, couldn't believe their ears. They had never heard anything like it. I was

later tour manager with them - I know what they thought.

"Anyway, this gave Hawk a unique sound - like it was another dimension. It was

raw. Vital stuff."

As is Johnson's bass, throughout the various movements of African Day.

With Hawk flying high, a manager had appeared on the scene - smart-talking Geoff

Lonstein - and a record deal had been struck with EMI-Parlophone.

It was a dream come true.

But Lonstein caused problems.

Keith Hutchinson recalls: "I went to war with Lonstein. We were playing to

packed houses everywhere. The show was massive. We were successful. People liked

us. But we weren't getting what we deserved.

"Money came in, but not to us.

"There were times when I had to hitch from the farm to Highlands North because I

didn't have money. Sometimes I walked - and that was pretty far. We came away

with virtually nothing in our pockets.

"Then one day I'd had enough.

"We were in the middle of a rehearsal. I stopped it - That's it, guys, I said.

No more. We are not going to do this any more. It's enough.

"Someone must have called Lonstein - half an hour later he arrived to try and

sort it all out.

"For a while it seemed okay. But then three months later, I quit."

I hear this graduate of the Royal School of Music chuckle over the telephone:

"One thing - I learned how to play a saxophone and flute. African Day was a good

concept - it was fun at the time."

Apart from African Day, as the side one concept, Hawk began writing more tracks

- Richard Johnson with Happy Man, Ornellas with Look Up Brother, Keith with Love

Song, Ornellas and Spook with Kissed by the Sun - and an evocative cover version

of George Harrison's Here Comes the Sun.

Look Up Brother, with its evocative solo acoustic lines, supplemented suddenly

by a second guitar, and building up to a vocal climax, is one of the most

beautiful songs penned.

Kissed by the Sun - "I wrote it in the swimming pool" says Ornellas, is another

gem, with Spook providing the melody.

Another version of the song is included in this reissue of the album. It is one

of four bonus live tracks recorded at a Concert for Hugh Tracey's International

Library of African Music on 10th June 1971, at the Selbourne Hall, in

Johannesburg (courtesy of Dave Marks' 3rd Ear Music)

The other three tracks are a previously unrecorded African Rondo, a spectacular

run through The Hunt and another version of Look Up Brother.

Ornellas says: "The album was simple really - kind of contemporary folk-rock. It

came out, we were happy. Then Lonstein turned us into a multi-voiced, huge

ensemble that destroyed the simplicity" - Ornellas uses that word often - "we

had strived so hard for, and which had become part of us.

"It was a disappointment."

Kahn says: "The other day Richard and I were talking - we see quite a lot of

each other. We kind of both came up with the same thought. Someone had been

talking about Clive Calder and the major success he had become - he is perhaps

the biggest record company executive in the United States today.

"Not bad for someone who had this little downtown Johannesburg office and a

company called CCP - Clive Calder Productions. You remember - had artists like

Richard John Smith?

"Well, Hawk at one time had this choice - either go with Lonstein, or sign with

Calder.

"We went the wrong way. We signed with Lonstein. Someone said, Better the devil

you know than . . . well, you know the rest. What would have happened to us

today? I guess it's a question that has no answer . . ."

We talk briefly about another former South African, regarded today as perhaps

the world's greatest record producer - the reclusive Robert John "Mutt" Lange.

But the talk is wishful.

Johnson just says: "Lonstein took the magic out of the band . . ."

But Braam Malherbe talks of magic - and indeed without his drum work, African

Day would not have been the barnstorming success it became.

He says: "They were magic years. This was jungle music."

But then Braam was brought up on the likes of Jon Bonham (Led Zeppelin) and

Keith Moon (The Who). "I learned those solo pieces," he says, "I could play

them. I'm a rock and roller.

"Jungle music is close to my heart - and no-one today can do it, other than

musicians from the Congo. It's alive and well there. Colin Pratley" (former

drummer with Freedom's Children) "feels the same way. He has that excitement

too. It's in his work."

Malherbe adds another dimension, however, to the Hawk story.

"It was political, you know. I mean there's that elephant destroying things

left, right and centre - driving people from their land. We were making a huge

comparison - if anyone had analysed the words then, they'd have realised what we

were on about.

"But when we played the small centres, people jeered and mocked us for wearing

long hair, while they walked around in safari suits with combs stuck in their

socks."

Braam says: "Perhaps the problem was that we didn't write hit parade stuff. It

was far too complex and deep for that - hey, no DJ would play the entire album."

There is another consideration. Radio play was strictly monitored - words had to

be supplied with the albums touted by recording company representatives, seeking

air time. Too often records were banned.

Malherbe says: "I enjoyed that time. It was magic."

Ornellas says: "Suddenly, in 1972, we had that unsung giant of South African

music, Ramsay McKay with us. Les 'Jet' Goode, who had been playing with the

British group Jericho, joined us in the place of Richard Johnson. The

extraordinary Julian Laxton, who had been flirting with Freedom's Children and

drummer Ivor Back was taken on.

"In a flash, we had a whole lot of Black musicians too - Alfred 'Ali' Lerefolo

came in on African drums and vocals, as did Billy 'Knight' Mashigo, who also

handled percussion. There was Audrey Motaung on vocals with Peter Kubheka."

Instead of a group, they had become a collective. A marketing proposition, with

prospects of becoming a commercial giant. For Lonstein.

Richard remembers the split of the original lineup with a touch of sadness "This

was heavy stuff. Both Braam and I lost our places in the band which had nothing

to do with the music. It was the machinations and scheming of the management.

"Leaving the band in this way hurt really badly as we were a few weeks away from

recording the second album."

Although the new lineup went on to record the Africa, She Too Can Cry album and

toured Europe to critical acclaim the long awaited breakthrough failed to

materialise and the group splintered in a blaze of publicity and recriminations

but that, as they say, is another story sometime to be told.

The original band reformed a couple of years later.

But things had changed.

Today the Hawks are active in many fields:

· Dave is a committed Christian pastor whose children have the Ornellas musical

genes;

· Richard is a successful businessman in Johannesburg;

· Keith was an integral part of Johnny Clegg's Savuka and now runs a recording

studio as does Mark "Spook " Kahn

· and Braam Malherbe is deeply involved in his other passion, training horses.

Now, over thirty years later, the reissue of African Day stands as a testament

to the collective magic of five musicians who drew inspiration from the red dust

of Africa and created a musical epic that surely must rank with some of the

greatest rock debut albums of all time.

Owen Coetzer, Cape Town 2001/2001

Janine Erasmus - 19 August 2008 http://www.mediaclubsouthafrica.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=635:johnny-clegg-190808&catid=43:culture_news&Itemid=53

Ubuhle Bemvelo (beauty of nature) was

released in 1982.

Clegg receives his honorary doctorate

in music from Wits University.

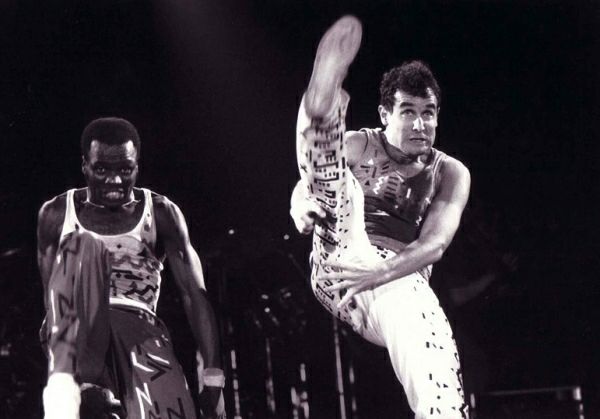

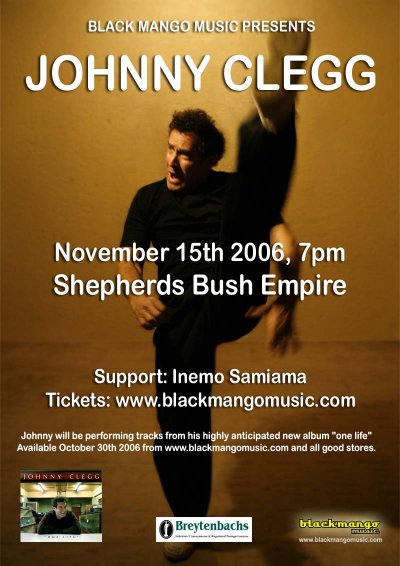

A poster for a concert in the UK shows

Clegg in full indlamu flight.

Clegg demonstrates a dance move during

a visit to Dartmouth College, US, where he

delivered a lecture on Zulu culture in 2004.

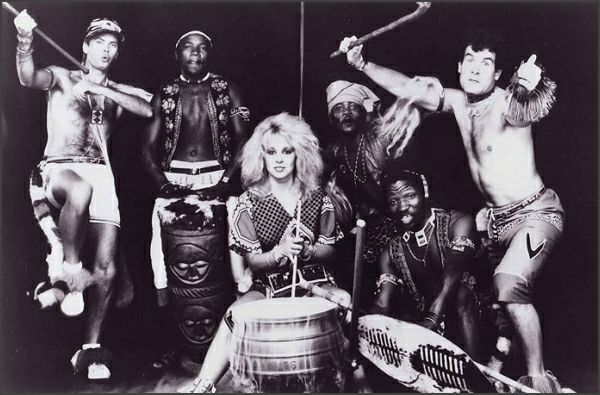

An early picture of Juluka. Sipho Mchunu stands at the back, while Clegg is front left.

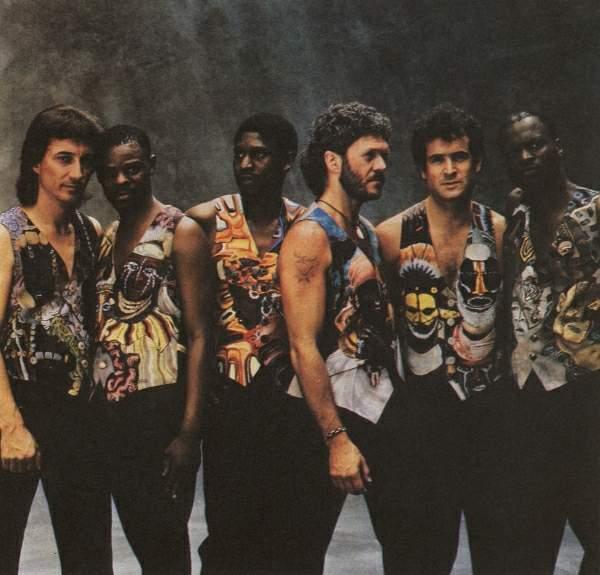

South African music icon Johnny Clegg takes to the local stage again in September, in a new production titled Heart of the Dancer. Clegg is a trailblazer in South Africa’s music industry, having cofounded Juluka, the country’s first racially mixed group, with Sipho Mchunu in 1979, and thereby changing the face of South African music.

After a successful run in Johannesburg, Heart of the Dancer is set to take Cape Town by storm, playing two shows in September 2008 at the Cape Town International Convention Centre. The show takes a look at Clegg’s career, and particularly the role that dance has played in his music and live performances.

Clegg has used various styles of traditional dance in his songs, each style imbuing his live shows with excitement and energy. Today, at 55 years of age he still dances as enthusiastically as ever, although he jokes that the muscles “get a little sore”.

As a solo artist, with his Juluka (isiZulu for "sweat") collaboration with Mchunu and his later group Savuka (isiZulu for "we have awakened"), Clegg combined traditional African musical structures with folksy Celtic lilts and rock music to create an accessible and hugely successful world music sound. At the same time he managed to encourage deeper respect for Zulu culture.

In the liner notes for the 1992 recording of Juluka’s performance with Ladysmith Black Mambazo at the Cologne Zulu Festival, Clegg was described as “symbolising the positive utopia of a freely integrated society”. In 2007 he received an honorary doctorate of music from his alma mater Wits University. The citation read, “Johnny Clegg's life and productions give meaning to the multiculturalism and social integration South Africans yearn for.”

The indlamu is a Zulu dance performed traditionally at celebrations such as weddings. Derived from the war dance of Zulu warriors, it is danced by men and calls for full traditional dress and the accompaniment of drums.

The dance is characterised by dancers lifting one foot high above the head, and bringing it crashing down to the ground. Clegg and Mchunu would perform this dramatic movement to enthusiastic acclaim from audiences worldwide in songs such as Impi, which tells the story of the battle of Isandlwana. In KwaZulu-Natal on 22 January 1879 British forces were slaughtered by Zulu warriors in the largest single military defeat of the British Empire ever, although it was a Pyrrhic victory for the Zulus. An impi is a body of armed men - not necessarily Zulus.

Other dance styles used widely by Clegg include the ibhampi, a lighter form of the indlamu where the dancer lightly bumps his foot down, and the inqo-nqo, which evolved in the crowded hostel environment. Here the dancer lifts his foot only a little way off the ground, brings it down hard enough to make an audible sound, and then throws himself backwards to land on his bottom.

Clegg, a social anthropologist who completed an honours degree at Wits University, was born in 1953 in Rochdale, near Manchester, England. When he was a year old his father left home and was never seen again. His mother moved to then-Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, her homeland, before moving to Johannesburg. Clegg was seven at the time.

While still in his teens he encountered the culture of the Zulu migrant workers who lived in Johannesburg hostels. Mentored by Charlie Mzila, a flat cleaner by day who played music in the street near Clegg’s home in the evenings, the youngster became fluent in isiZulu, the Zulu language, and mastered the maskandi style of guitar-playing. He also gained a deep understanding of and respect for Zulu culture, later earning the nickname White Zulu.

So interested was the young Clegg in the hostel musical culture that he often entered such premises illegally, as the Group Areas Act was still in force, and even took part in dance competitions.

Around this time Clegg met gardener and musician Sipho Mchunu, a migrant labourer from Kranskop in KwaZulu-Natal. The two formed an acoustic musical duo which later grew into the successful group Juluka, named after a bull owned by Mchunu – but which also implied that much of South Africa’s wealth was built on the sweat of migrant labourers. The group’s first release was Universal Men in 1979.

“Universal Men still sounds fresh,” said the late bass guitarist Sipho Gumede, who performed on the album, in 2000. “It's one of those albums that will be there for life. It was an innocent album. We went into the studio with the aim of making great music. No one was thinking about how many units we would sell. We just thought about the music.”

Juluka contravened the apartheid laws of the time and the authorities took a dim view of the group. Clegg and Mchunu were arrested on a regular basis and their music was censored and banned, but they pressed on regardless, fighting against the system in their own way. Their music was a statement of political defiance. Songs like Asimbonanga from the 1987 album Third World Child and One (Hu)Man, One Vote from 1990’s Cruel Crazy Beautiful World carried profound messages, as did many of Clegg’s songs of the time.

The iconic song Asimbonanga ("we cannot see you") was a call for the release of Nelson Mandela and paid tribute to other heroes of the liberation struggle such as Steve Biko, Victoria Mxenge, and Neil Aggett.

Released in 1990, One (Hu)Man, One Vote was Clegg’s reminder that voting is a basic human right that was denied for so long to millions of South Africans. "The right to vote has become a hassle for a lot of people in the West, it’s taken for granted," Clegg said of the song. "With One Man, I tried to emphasise that this is a universal right that people fight and die for in other parts of the world."

Juluka disbanded in 1985. Clegg immediately formed another band, Savuka, which was a direct response to the tense situation in South Africa at the time and featured a more conventional pop-rock sound as well as more explicitly anti-apartheid songs. Savuka was launched just one month before South Africa declared a national state of emergency in 1985. The group began touring abroad extensively and by the end of 1987 was the leading world music group touring the francophone countries.

Savuka broke up in 1994 after great international success, including a 1993 Grammy nomination for best world music album for its final release Heat, Dust and Dreams. Clegg felt that the group had lived up to its name. "The Savuka project is over," he said in 1996.

Juluka reformed for a short time, and Clegg and Mchunu released their last album as Juluka, Ya Vuka Inkunzi (The Bull has Risen) in 1997.

Clegg then embarked on a solo career, releasing albums such as New World Survivor and One Life. The latter, released in 2006, features the singer’s first-ever Zulu/Afrikaans tune, Thamela. The album also included the anti-Mugabe statement The Revolution Will Eat Its Children (Anthem for Uncle Bob).

“The private and political choices we make affect how our one life influences the greater whole,” said Clegg of the album, ”and so the songs look at the politics of betrayal, love, power, masculinity, the feminine, survival and work. We each have a story to tell and many of the songs take on a narrative structure to emphasise the story telling nature of how we make meaning in the world.”

In spite of the political nature of many of his songs, Clegg has never viewed himself as political. "It’s very important to understand that I’m not a spokesman for South Africa,” he said in 1990. “All I’m doing is describing the South African experience. There are already too many politicians in South Africa; it doesn’t need another."

Clegg is a published academic, with papers such as “The Music of Zulu Immigrant Workers in Johannesburg: A Focus on Concertina and Guitar” and “Towards an understanding of African Dance: The Zulu Isishameni Style”, published in 1981 and 1982 respectively.

He was honoured by the French government with its Chevalier des Arts et Lettres (Knight of Arts and Letters) in 1991, and in 2007 received an honorary doctorate in music from Wits University.

Marie-Line, marquée

à vie par le concert de Johnny Clegg

Marie-Line, marquée

à vie par le concert de Johnny CleggInauguré en décembre 1985, le stade couvert régional de Liévin s'est fait un nom avec le meeting international d'athlétisme, mais il est loin de ne se résumer qu'à ça. Les souvenirs de Marie-Line, mémoire des lieux, en témoignent....

Embauchée à l'ouverture du stade en 1985, Marie-Line a tour à tour géré le

secrétariat, la paie et la comptabilité. Aujourd'hui, à 51 ans seulement, elle

est la mémoire des lieux, « l'ancêtre » comme disent ses collègues. L'histoire

du stade n'a pas de secret pour elle.

Marie-Line peut quasiment retrouver le mois et l'année de tous les gros concerts

qui ont fait vibrer la scène liévinoise. Enfermée dans son bureau la journée,

l'employée, aux premières loges, applaudissait le soir les artistes. « Jusqu'à

la naissance de ma fille en 1995, j'ai assisté à tous les concerts. J'ai juste

raté Peter Gabriel car j'étais en vacances. Miles Davis, à l'automne 86, a été

le tout premier », raconte-t-elle. Mais spontanément, avant de lister tous les

chanteurs qui ont foulé la scène du stade couvert, elle évoque Johnny Clegg, en

juin 1988. « C'est le concert qui m'a le plus marquée. C'était fou. On voyait

encore arriver des marées humaines alors que le stade était déjà complet. Les

pompiers, le commissaire, le maire, tout le monde avait peur qu'il y ait un

drame. Mais heureusement tout s'est bien passé. Le maire a soufflé quand le

dernier spectateur a quitté les lieux. » Fan de Sardou, Marie-Line l'a vu trois

fois, comme elle a vu aussi Goldman, Julien Clerc, Johnny, The Cure ou

Starmania. Son rêve maintenant que le stade s'est refait une beauté et que ses

filles ont grandi ? Barbra Streisand.

G.C.

Johnny Clegg

Johnny Clegg s'initie à la guitare à quinze ans mais c'est sa rencontre avec un musicien de rue zoulou qui lui permet d'apprendre les rudiments de la musique africaine et le Ihhlangwini. Il n'hésite pas à braver l'interdit en accompagnant son ami dans les différents centres de travailleurs immigrants réservés aux noirs. C'est là qu'il se forge une solide réputation et qu'il prend conscience du fossé creusé par l'apartheid.

Portrait

Johnny Clegg, né

en 1953 à Bacup au Royaume-Uni dans une famille aisée, déménage en 1960 dans les