22.03.2008

http://ejmas.com/jalt/jaltart_Coetzee_0902.htm

InYo: Journal of

Alternative Perspectives Sept 2002

By Marié-Heleen Coetzee

Copyright © Marié-Heleen Coetzee 2002. All rights reserved.

1a. Introduction

The Zulus are one of the Nguni people of South Africa. Linguistically and culturally, the Xhosa, Pondo, and Thembu are Southern Nguni, while the Zulu, Swazi, and Ndebele are Northern Nguni.

During the 1810s, a Zulu leader named Shaka kaSenzangakona established an empire in northeastern South Africa whose military relied on phalanxes rather than skirmish lines. His armies were highly successful, and within a few decades, his style of warfare spread as far north as Lake Tanganyika.

Although Shaka was assassinated in 1828, his kingdom survived until 1879, when it was destroyed by the British, who feared a Zulu attack on the white settlements then expanding outward from Durban. The Zulu culture, however, survived into the present, and today there are about 8.8 million Zulus, most of whom still live in KwaZulu-Natal. (The name Natal is owed to the Portuguese explorer, Vasco da Gama, who reached its coast on Christmas Day, 1497.)

The genealogy of the presumed originators of Zulu stick fighting is traced to Amalandela, son of Gumede, who inhabited the Umhlatuze valley about 1670 (Werner, 1995:28). The exact location of Amalandela’s former habitat remains an enigma.

According to Bryant (1949:3), Amalandela was a member of the Ntunga Nguni clan. According to Dalrymple (1983:74), he fathered two sons, respectively named Qwabe and Zulu, and the latter gave his name to the Zulu people.

The recent history of stick fighting is traced to the legacy of the Zulu king Shaka. Shaka lived from 1787 to 1828, and during his reign, he established the Zulu Empire and became Southern Africa’s most legendary warrior-king.

Until recently, historians credited Shaka with the development of Zulu warfare, with its emphasis on stabbing spears and phalanxes, but recent research suggests that the weapons, strategies, and tactics accredited to him were established before his rise to power. The great warriors preceding Shaka, like so many historical figures and events, are hidden from documented history, and forgotten even in the oral traditions.

Nonetheless, it is generally agreed that during Shaka’s reign, stick fighting was used as a means of training young men for both self-defence and war. Shaka himself, in Ritter’s version of the story, was already a highly proficient stick fighter at the age of 11 (1957:14).

2a. Introduction

Zulu stick fighting provides an opportunity for men to build courage and skill, to distinguish themselves as proficient warriors, and to earn respect in the community (Ntuli, Interview, 1996). Leitch (Interview, 1996) is of the opinion that the techniques and manoeuvres applied in stick fighting are identical to those implemented during traditional Zulu warfare, the only difference being the weapons used. Nonetheless, stick fighting is a game, and the dynamics of stick fighting are generally playful. The exceptions are when sticks are used for self-defense or in a faction fight, or when amashinga (professional stick fighters) compete.

2b. Nineteenth Century

According to Ntuli (Interview, 1996), Shaka (reigned 1816-1828) rewarded good and courageous stick fighters with cattle, terming the practice ukuxoshisa. Ntuli further postulates that the relationship of stick fighting to military practice was still prevalent during the time of Shaka’s successor Dingane, who ruled until 1840 (e.g., into the era of early white settler encroachments into the interior of KwaZulu-Natal). Ndlela kaSompisi, commander-in-chief of Dingane’s army and senior induna (prime minister) to Dingane, was arguably the most important figure in Zululand after the king (Becker, 1964:69). Certainly Ndlela’s experience and skill in stick fighting assisted him in climbing the military ladder, and helped him earn a distinguished reputation. Ntuli (Interview, 1996) is a direct descendant of Ndlela.

During the lifetime of the next major Zulu king, Cetshwayo (1836-1884), stick fighting was an accepted means of resolving the internal disputes (Laband, 1995:178). During this era, combatants used the shafts of spears in a stick fight, but not the blades (Laband, 1995:178). Additionally, stick fighters were to follow a code of conduct, as stick fighting, unlike warfare, was not intended to cause loss of life.

Laband (1995:178-179) describes an unusual event in which the protocol of stick fighting was breached. The occasion was a stick fight between two of Cetshwayo’s regiments (amabutho). This fight took place on December 25, 1877, during the UmKhosi, or advent of the first fruits, festival. It seems that Cetshwayo crammed his favourite iNgobamakhosi regiment (ibutho), consisting of young, unmarried men, into the same quarters as the uThulwana ibutho, which was made up of older, married men. Cetshwayo and some of his brothers belonged to the older ibutho. The younger men apparently did not respect the customary power relations between themselves and their elders, and were dissatisfied with arrangements concerning the reception of wives of the uThulwana. The rising levels of antagonism between the two parties eventually led to a physical clash. The older uThulwana ibutho intentionally disregarded an accepted convention by attacking the iNgobamakhosi with spears after an initial defeat by the iNgobamakhosi. For their malpractice, Cetshwayo prohibited the uThulwana from further participation in the festivities, and in addition,the men were fined "a beast all round" and sent home.

Although the British effectively ended Zulu military power in 1879, stick fighting apparently continued to play a political role throughout the lifetime of the Zulu king Dinuzulu (1868-1913). Ntuli believes that in Dinuzulu’s times, a skilled stick fighter was appointed to train the heir to the throne in the art of stick fighting (Interview, 1996). Thus, the king’s leadership abilities and his potential as a military commander were judged according to his (presumably superior) martial prowess.

In Shaka’s time, stick fighting was used as training for warfare. However, during subsequent years, Zulus began using stick fighting to represent conflict resolution on a symbolic rather than military level. This form of symbolism still appears in the inter-district umgangela, or stick fighting competitions, held in rural areas such as Nongoma. Still later, stick fighting came to function as an expression of Zulu ethnicity, and to show political affiliation with the Zulu-dominated Inkatha Freedom Party (Mnqayi, Personal Communication, 1998).

Leitch (Interview, 1996) argues that this decontextualisation and exploitation of stick fighting for political gain has negatively affected perceptions of the art. For example, crowds misuse elements of stick fighting during marches in cities, or use their fighting sticks to express ethnicity. This association of stick fighting with violence and riots negates its profundity and beneficial social implications, and accordingly, many Zulu people distance themselves from the art (Mnqayi, Personal Communication, 1998).

Leitch (Interview, 1996) also believes that instances where crowds run out of control parody the traditional function of stick fighting in society. Control, respect, and accountability lack in such marches, whereas they are of the utmost importance in a stick fight. Qoma (as cited by Krog, 1994:42) states that the use of sticks became politicised to the extent that any African person carrying a stick is classified a "violent Zulu". As such, a practice that once played an instrumental role in building the pride of a nation has come to be regarded with contempt by some (Ntuli, Interview, 1996).

In the Tugela Basin and the South Coast (different areas than where I did my research), stick fighting has all but disappeared. Stick fighting is practised less frequently than in the past in KwaDlangezwa and Ongoye, too, apparently due to its association with recent violence (Mnqayi, Personal Communication, 1998). Leitch (Interview, 1996) believes that traditional stick fighting is nowadays only found in areas where there is little political friction.

Nonetheless, traditional stick fighting still takes place in some of rural areas of KwaZulu-Natal, where it continues to act as a process of socialisation, and to transmit the social norms of the community in which it operates. Therefore, while the practice of stick fighting is constantly modified by changes in the social system, it can still serve as a vehicle for mastering the body and mind, and be instrumental in nurturing the practitioner’s dignity and pride as a man (Ndaba, Interview, 1996).

In the immigrant communities of Johannesburg, migrant Zulu workers sometimes teach stick fighting as a martial art. Meanings derived from these interactions are primarily related to sportsmanship (Qoma in Krog, 1994:42), and lack the integral social affiliations of traditional stick fighting. Stick fight demonstrations offered to tourists, such as at Shakaland (Home-video recording, 1996), are performances.

Long past its days of glory, stick fighting is no longer a common practice among the Zulu people, and practitioners struggle to validate its existence in these days of political turmoil, acculturation, and modernisation. Nonetheless, stick fighting appears to assist in upholding the traditional social system by perpetuating socially accepted modes of male behaviour and ideals. Stick fighting, as a cultural tradition, therefore continues to fulfil its traditional didactic function in some Zulu communities.

3a. Introduction

Zulu men traditionally owned fighting sticks (izinduku). The sticks were stored in the roof of a house, and were carried for self-defence or used when the owner was challenged to a stick fight (Ntuli, Interview, 1996).

Adult males often owned several fighting sticks, and from these, they selected a pair to fight with (Ndlangavu as cited by Krog, 1994:42).

At the age of about 16, a Zulu boy’s father took him into the forest to choose and cut his own fighting sticks from trees. (Fighting Sticks, Episode 2, [S.a.]). As an adult, a man might make his own izinduku or employ a specialist to do so. Apartheid laws prohibiting South African people of colour from owning guns or displaying traditional weapons in public led to the use of instruments such as umbrellas and ordinary walking sticks as substitutes for traditional izinduku (Fighting Sticks, Episode 1, [S.a.]). Nonetheless, the practice of carrying sticks still prevails in some rural areas of KwaZulu-Natal, such as KwaDlangezwa.

Izinduku may differ in appearance according to their region of manufacture (Mzobe, Interview, 1996). However, regardless of appearance, izinduku must be stout enough to withstand the impact of blows from an opponent’s weapons.

Although the choice of wood for fighting sticks is often specific to the practitioner’s family lineage, (Fighting Sticks, Episode 2, [S.a.]), various local trees are suitably strong for use as fighting sticks. Thus, izinduku are made from trees such as the umqambathi, umazwenda, ibelendlovu, umphahla (Ntuli, Interview, 1996), umthathe, and umunquma (Ndlangavu as cited by Krog, 1994:24). [EN1]

Decorations on izinduku are for aesthetic purposes or to identify members of the different sides in a regional stick fight (Zulu, Interview, 1996). Decorations on the fighting sticks of informants observed at Nongoma include painted patterns, beadwork, and pieces of cloth.

For faction fighting and war, there are a number of sticks available. Examples include the short stabbing spear or iklwa, the swallow-tail axe or isisila senkonjane, the isizenze axe used by commoners, and the long spear named isijula (Derwent et al., 1998:86). The knobkerrie, or iwisa and isagila, is also available. Stick fighters, however, make use of two specific sticks in single combat.

The first stick is the offensive fighting stick, or induku. [EN2] This is a strong stick or shaft of wood without a knob carved smooth and used specifically for stick fighting.

The length of the induku depends on the physical stature of its owner, but is generally about 88 centimetres in length. The induku’s circumference increases slightly from bottom to top, and the extra weight that the head carries enhances the mobility of the stick during offensive manoeuvres.

The induku is held in the right hand, and used to strike at the opponent’s body and head. [EN3] A piece of cowhide can be tied around one end of the stick to secure the fighter’s grip on the weapon, and the whisk of a cow’s tail can be tied around the bottom of the stick to hide a sharp point. Although this sharp point can be used for stabbing, doing so is not considered appropriate during an honourable stick fight.

3d. Blocking Stick (Ubhoko)

Ubhoko or blocking stick, is a long, smooth stick that tapers down to a sharp point. As a defensive weapon, it is skilfully manoeuvred with the wrist of the left hand, and used to protect the body of a combatant from the opponent’s blows. Although its length depends on the physical stature of its owner, the ubhoko is meant to ensure protection from head to foot, and so is notably longer than induku. Ubhoko is generally about 165 centimetres in length. Like induku,ubhoko’s circumference increases from the grip upwards.

Although the ubhoko could be used as a stabbing weapon, in a stick fight, protocol demands that it be used exclusively for the purpose of defence. The action of defence with ubhoko can be referred to as ukuvika or ukuzihlaba (Mzimela, 1990:12).

Another short stick, umsila, is held in the left hand together with ubhoko. Not used for fighting as such, it is used instead to uphold the small shield, or ihawu, that protects the left hand. (The umsila runs vertically down the middle of the shield through four triangular nooses, and tapers to a point.) Fighters in Nongoma maintain that umsila is also used to protect the face during a stick fight. As an aesthetic accessory, Nongoma fighters tie strings of antelope skin to the top of umsila.

Ihawu is a relatively small and oval shaped piece of cow skin, held in the left hand. During Shaka’s regime, warriors were ranked by means of the colour of the shields they carried (Fighting Sticks, Episode 1 [S.a.]), but this convention is seemingly not evident in the choice of shields used for stick fighting.

There is no set size for ihawu, although it should be large enough to protect the hand and wrist, and small enough not to impede on ubhoko’s mobility. As a rule, however, the shield used for stick fighting is between 55 centimetres and 63 centimetres long, and 31 to 33 centimetres wide. A handle big enough to hold two or three fingers (the index, middle, and ring fingers) is located at the back of the shield, left of the umsila. Fighters first clutch the handle with two or three fingers before placing ubhoko in the left hand.

A soft cushion is placed on the inside of the shield to ensure that the hand remains protected from an opponent’s blows. Traditionally, this cushion was made from sheepskin, and called igusha. In contemporary times, sponge or other soft material, named isibhusha, has been utilised as a protective measure inside the ihawu (Zulu, Interview, 1996).

4. Traditional Medicine (Intelezi)

4a. Introduction

Traditionally, Zulu stick fighters prepared for a fight using medicine (intelezi) prepared by a herbalist (inyanga). In contemporary times, the widespread use of intelezi has been inhibited by changes in the social and religious structure of Zulu communities (Zulu, 1996). This is probably due to European and missionary influences.

Krige (1965:329) identifies intelezi as "the generic name for all medicinal charms, the object of which is to counteract evil by rendering its causes innocuous". Intelezi is also a collective name for a variety of sprinkling charms. The kind of traditional medicines used on sticks vary according to specific purposes, and specific ingredients are necessary for the outcome required (Stewart, Interview, 1996). Specific intelezi used for stick fighting assist in warding off evil, going into battle at a psychological and physical advantage, weakening the opponent, and strengthening sticks.

Before battle, Zulu armies underwent cleansing rituals conducted by inyanga (herbalists) and/or isangoma (diviners). A very important aspect of this preparation involved the sprinkling of the warriors and their weapons with a certain intelezi the day before the battle (Stewart, Interview, 1996). Krige (1965:272) points out that the process of sprinkling, called chela in Zulu, could also take place just before a battle commenced. Krige (1965:272) provides a detailed description of the ritual procedures related to the cleansing and strengthening of warriors.

Intelezi is not used exclusively for battles. For example, stick fighters often use intelezi to strengthen their sticks before accepting a challenge. Reportedly this increased the strength of the sticks in order to withstand attacks, and multiplied the impact of the offensive blows (Ntuli, Interview, 1996). Other intelezi can reportedly cause dizziness, strokes, or impair the vision of an opponent (Mzobe, Interview, 1996). My personal sample of intelezi prepared by an inyanga in KwaDlangezwa in December 1998 contained a silvery ingredient said to cause bright flashes to appear before the opponent’s eyes, thus distracting him and negating his concentration.

4d. Rituals Associated with Stick Fighting

The intelezi rituals used before a stick fight bear a striking resemblance to the rituals associated with traditional Zulu preparations for warfare. For example, on the day preceding an umshado or wedding ceremony, sticks are treated with intelezi and left overnight outside the home (Mbanjwa, Interview, 1996), usually at one end of the cattle enclosure (Stewart, Interview, 1996). When two unrelated groups of men prepare for a clash, the ritual proceedings take place at the home of an induna (local leader). Again, the sticks are kept in the intelezi until the next morning (Ntuli, Interview, 1996).

The sample of intelezi obtained by Mnqayi is a brown powder. Details regarding the application of intelezi are subject to notable differences in opinion, but informants generally agree that the intelezi is mixed with water and placed in an ordinary clay pot (Stewart, Interview, 1996). On the morning of the fight, the stick fighters go to the cattle enclosure, where they make use of the intelezi (Mbanjwa, Interview, 1996).

Vusi Buthelezi (Interview, 1996), the inyanga yemithi at Dumazulu, explained that the intelezi is sprinkled on the weapons in the cattle enclosure in acknowledgement of the congregation of ancestors inhabiting the territory. Alternatively, the izinduku are placed in the intelezi, which is washed onto the weapons with a broom (Mbanjwa, Interview, 1996) or dipped into the medicine (Ntuli, Interview, 1996). Some fighters also drink the intelezi.

In a powder form, intelezi may be administered through small incisions in the skin called ingcabo. This manner of applying intelezi forms part of the fighter’s preparation for the contest. Buthelezi (Interview, 1996) states that ingcabo are made on:

Small quantities of intelezi in powder form are taken orally in small quantities, usually after mixing it with sugar and then eating the mixture from the palm of the hand. This method reportedly provides the stick fighter with psychological and physical strength.

During the fight itself, intelezi are put inside a leather band that is tied around the biceps for the duration of the fight (Fighting Sticks, Episode 2, [S.a.]). Finally, some stick fighters place the bark of the uphindamshaye climber under their tongues, chew on it, and then spit it onto the opponent during a fight (Mzobe, Interview, 1996).

Like fighters, sticks are routinely treated with ritual medicines. For example, the use of menstrual blood or snake venom is considered a dangerously potent stratagem.

Historically, menstruating Zulu women were considered unclean, and a number of social taboos had to be respected during the menstruation period (Krige, 1965:82). The Zulu people believed that a woman lingers in a marginal state of existence during menstruation; she does not completely surface in life or death, but abides in a state of transition (Clegg, Personal Communication, 1996). In intelezi relating to stick fighting, menstrual fluids are combined with a number of other medicinal substances, and then applied to the sticks. This allegedly renders the opponent’s defence impotent (Zulu, Interview, 1996). The use of menstrual blood on sticks is known among stick fighters at Nongoma. However, according to Clegg (Personal Communication, 1996), this practice is more prominent in the province that was known as Natal prior to the 1994 elections than in the province that was known as KwaZulu before the elections.

Mzobe (Interview, 1996) explains that snake venom, especially that of the mamba and the cobra, can be utilised as protective medicine for sticks. Medicine relating to the use of snake venom is termed isibiba (Zulu, Interview, 1996). To paraphrase Mzobe’s statements, a snake is barbecued and its body ground up, then mixed with fat and smeared onto the fighting sticks.

4f. Associated Medicinal Plants

To keep opponents from working counter-spells, the exact nature of the medicinal plants used for intelezi is secret.

Nonetheless, some generalisations are possible. For example, the ingredients generally consist of a number of herbs and plant extracts, and an inyanga can obtain ingredients for the medicine from as far afield as Zanzibar (Mzobe, Interview, 1996). To give a second example, one kind of intelezi consists of the climber uphindamshaye and the uphind’umuva cut into pieces, then mixed together with a small aloe named cene and the roots of the uMazwende tree (Buthelezi, Interview, 1996). [EN4]

Intelezi can be bought from an inyanga. In the past, herbalists were offered cattle for the service of preparing the medicine to strengthen the sticks of the combatants. Nowadays money is acceptable as payment for the inyanga’s assistance (Ntuli, Interview, 1996). Intelezi can still be bought in rural areas of KwaZulu-Natal or informal trading areas such as taxi ranks. The prices in KwaDlangezwa in 1998 ranged from R400 to R2 000 (about US $40-$200) depending on the availability and geographical location of medicinal plants, and the sort of plant or animal extracts used (Mnqayi, Personal Communication 1998). An inyanga can specialise in the field of fighting intelezi, and be consulted exclusively for such purposes. It is not necessary for the inyanga to apply the intelezi personally to the sticks or fighter, only to prepare it.

Intelezi, or medicine, is intimately associated with traditional Zulu stick fighting. However, as stated earlier, it seems as if the widespread use of intelezi has been inhibited by changes in the social and religious structure of Zulu communities, possibly due to increased urbanisation and Westernisation.

5a. Introduction

Tyrell and Jurgens (1963:111) point out that Zulu children did not receive much formal education designed to mould them for their roles in traditional society. "Traditional education for the individual constitutes a gradual absorption into society and the acquisition of certain skills and behaviour patterns". In this world, informal stick fighting was one of the "skills and behaviour patterns" that instructed Zulu males about the social roles, qualities, and behavioural patterns expected of them. Younger boys fought with sticks while tending herds, while older boys and young men sparred publicly at ceremonies and festivals (Mzobe, Interview, 1996). The practice of sparring with sticks is called ukungcweka, and it differs from a stick fight challenge (Msimang, 1975:166).

5b. Learning to Spar

From an early age, a Zulu boy was expected to look after cattle in the field, "exploring his manliness and independence in a world away from parental supervision". Part of this exploration involved a boy’s fighting his way up to a position of leadership among the other herders (Tyrell and Jurgens, 1983:11, 115). The way he did this was by defeating his age mates at sparring with sticks.

The intricate skills of stick fighting and sparring are learned by observation, imitation, and experience (Stewart, 1996). Very young boys train using switches or small sticks, and they practice their skill with the sticks on trees in preparation for fighting another boy. Fathers also instruct their little boys in the art by standing on their knees and sparring with the child (Stewart, Interview, 1996).

Sparring can be a daily occurrence amongst the herd boys. No specific amount of time is set aside for training; it occurs when the situation arises. Nonetheless, boys use every opportunity to spar and thereby establish their reputations as stick fighters and thereby prove their manliness.

To incite a sparring match, Ndaba (Interview, 1996) states that herd boys often engage in "verbal gymnastics". The competition and sparring does not have to take place according to age groups; older boys can clash arms with younger boys. Although this could lead to physical bullying, no one is compelled to take part in a game of sparring. According to Krige (1965:79), the recognised manner of challenging another herd boy to a sparring match is to tap him on the head with a stick and utter a daring verbal comment. Comments such as "I am your master" (iNgqotho) are considered invitations to a fight. The challenged then either prepares to fight or agrees with the statement and prevents a fight.

Sparring between herders takes place under strict supervision of the inqwele, or leader of the herd boys (Ntuli, Interview, 1996). The inqwele assumes his position of leadership after defeating all the opposition in the area during stick fights. Refinement of stick fighting skills is encouraged, as the other herders judge the proficiency of the combatants. An informal audience is thus present during the training process.

There are strict rules governing the sparring exercise. Partners sparring with the sticks do not aim to hit each other’s heads, and often do not use an ihawu (small shield). As such, a hit to the hand is a foul. Should any of the participants fall down or lose their stick, the sparring stops until sparring partners are on equal footing again. It is not necessary to use induku or ubhoko, and rough branches of trees are accepted substitutes for fighting sticks (Msimang, 1975:166). Exclamations indicating an acknowledgement of a hit (ngiyavuma) or requests to stop the sparring (khumu or malushu) are utilised for both sparring and combat, and are strictly adhered to.

No matter how important the role of sparring with sticks in the social construction of masculinity, it is an undesirable skill for females. Should a woman "jump over the sticks", especially during her menstrual cycle, misfortune is supposed to fall upon the owner of the sticks (Ntuli, Interview, 1996). Ironically, menstrual blood can be a potent medicine for strengthening the sticks when applied in conjunction with a number of other substances (Zulu, Interview, 1996). Nonetheless, Leitch (Fighting Sticks, Episode 1, [S.a.]) indicates that Zulu women can and will use this martial art when necessary. If a man has no sons to tend to the cattle, one of his daughters has to go to the field with the herd boys and she learns to stick fight with them. Tankiso Mafisa (Personal Communication, 1996) stated that her mother used to tend to cattle as a young girl, and stick fight with the boys.

6a. Playing Sticks (Ukudlalisa Induku)

Competitive stick fighting at festivals is called ukudlalisa induku, or "play sticks" (or alternatively, ukudlala induku, which roughly translates as "play sticks with you"). Although Msimang (1975:166) argues that by teaching methods, techniques, manoeuvres, and rules, sparring prepares the boys for fighting in single combat, Zulu stick fighting is essentially playful in nature.

Schoeman (1975:166) says that playing sticks at festivals such as the iphapu (lung festival) provide an opportunity for Zulu boys and men to experience first-hand different strategies, techniques, and rules. Derwent et al. (1998:36) argue that a challenge to play sticks can only take place at a wedding, but other sources contest this viewpoint. For example, stick fights challenges have been reported at the first fruits festivals (Clegg, 1981:8), the installation of a new traditional leader (Larlham, 1985:13), and inter-district fighting (Clegg, 1981:8). Stick fighting also occurs at social gatherings such as beer drinking (Stewart, Interview, 1996), an imbizo (Zulu, Interview, 1996), the iphapu festival (Schoeman, 1982:49), courtship (Stewart, Interview, 1996), and the thomba ceremony (Elliot, 1978:143). These sources do not indicate the nature of the combat, e.g., whether it was ukungcweka or a challenge.

Stick fighters begin to fight competitively at public ceremonies and social gatherings at about 18 years of age (Ntuli, Interview, 1996). The youngest fighters are about 15 years old, but it is unusual for a boy to start fighting publicly before he has fully passed puberty. When a boy reaches puberty, he receives a second name that is indicative of a contribution he made to the community (Stewart, Interview, 1996). This second name, or isithopo, may be self-composed or granted by peers and parents. Either way, the second name gradually develops into a personal izibongo that mediates an individual’s personal and social identity (Brown, 1998:87). This is mentioned because during a stick fight, the fighter is called by his second name, and his friends recite the story of how he acquired this second name (Stewart, Interview, 1996; Mzobe, Interview, 1996). Dumisani Mbhense (Personal Communication, 1996) points out that the recital of praises by the fighter’s peers is an enjoyable aspect of the action. Consequently, izibongo are statements of friendship among a combatant and his friends/family.

Leitch (Interview, 1996) points out that stick fighting is considered an activity for the young. Thus, a man will usually stop fighting in his mid-thirties, by which time he has earned respect as a proficient stick fighter. Older men assume responsibility for upholding the fabric of society, and become mentors to the younger men. Furthermore, to "retire" from stick fighting while your reputation as a fighter is intact is a means of ensuring that you remain respected as a warrior in your older days.

6b. Surrogate and Professional Stick Fighters

Although Zulu people consider it chivalrous to fight one’s own fight, it is acceptable to stick fight on behalf of another person. Such a person might be an aggrieved younger brother who lacks experience in the skill, or someone who is unable to fight at the time. For example, a migrant labourer can request a man back at home to fight on his behalf. As such, he does not have to leave his work to stick fight and settle the issue at hand (Fighting sticks, Episode 1, [S.a.]).

Stick fighting can also take place on a "professional level". Leitch explains that a professional stick fighter, or ishinga, travels around in search of stick fights (Interview, 1996). According to Mzobe (Interview, 1996), the term ishinga refers to a very brave and even rude person. Unlike "social fighters", to use Leitch’s (Interview, 1996) phrasing, an ishinga’s only ambition is to demolish the opposition and earn another victory as the top stick fighter. His only reward is social recognition. He normally uses well-worn fighting equipment, and has an unkempt appearance. Men tend not to fight him, since the element of play is seemingly lacking in the ishinga’s approach to stick fighting. Mzobe (Interview, 1996) states that in cities such as Johannesburg, amashinga can fight for prizes or money. However, social stick fighting normally does not have an economic reward for the participants involved.

7a. Introduction

Stick fighting takes place at different times, occasions, and places. As information about technical aspects of Zulu stick fighting appears in The Fight Master, 34: (2), 2001, it will not be repeated here. However, the rules and protocols of stick fighting deserve some attention.

For the most part, stick fighting takes place outside the cattle enclosure of a homestead (Ntuli, Interview, 1996). If a stick fight does take place inside the cattle enclosure, it is a fight among the men of that family, or umuzi. (Other people would not fight inside another’s cattle enclosure, due to the presence of a family’s ancestors in the enclosure.) However, should a stick fight be connected to the chief, then the fight might take place in his cattle enclosure (Stewart, Interview, 1996).

Other than this, there is no space specifically set aside specifically for stick fighting. Instead, a space is selected to suit the needs of the occasion (Leitch, Interview, 1996). In urban areas such as Johannesburg, stick fights take place on Friday or Saturday evenings in the hostels (Ndlangavu as cited by Krog, 1994:42).

The action and structure of a stick fight follow a common, recognisable pattern. The reason is that for Zulus, stick fighting is a gentleman’s game, and specific rules and protocol govern its practice. Breach of rules or protocol is unacceptable, as it indicates that the fighter does not have confidence in his own abilities to beat the opponent by the rules (Ntuli, Interview, 1996). A man only proves his supremacy at stick fighting in a fair fight, or "impi yamanqanu", where the rules are followed (Derwent, et al., 1998: 83).

Derwent et al. (1998:63) state that a stick fighter voices a challenge to indicate that he is ready for fighting. Elders should grant permission for a fight before any challenge is made. Mbhense (Personal Communication, 1996) calls a challenge "inselelo". At public ceremonies the warrior captain, or umphathi wezinsizwa, is supposed to regulate the activities, but induna sometimes fulfil this function (Mbanjwa, Interview, 1996).

The person regulating the fight should make sure that the correct sticks are utilised, that "the weight is the same, that there is no possibility of your adversary being unduly hurt" (Ndaba, Interview, 1996). His task is thus to ensure that the rules are followed, and that a fair fight takes place. Warrior captains can remain in command up to their late forties, and would only engage in a stick fight when forced to assert their authority (Leitch, Interview, 1996). A man fights his peers, and not someone significantly younger or older that himself.

Once people have gathered around the selected space, the stick fighters take turns demonstrating ukugiya (solo display of stick fighting skills) against imaginary opponents. Ukugiya derives from fighting in single combat, and is where each individual can display his own characteristic style (Dalrymple, 1983:160). Historically, ukugiya prepared fighters psychologically for warfare and reaffirmed the army’s superior skills, and today ukugiya still takes place before a stick fight (Leitch, Interview, 1996).

Ukugiya do not follow set floor- or step patterns (Dalrymple, 1983:160), and are usually accompanied with praises, called izibongo, and war cries and chants, called izigiyo (Gunner & Gwala, 1994:1). Izigiyo are characterised by a militaristic phallocentrism, and often liken men to powerful totems such as bulls or lions that are self-reliant and "fiercely individualistic" (Derwent et al., 1998:70,136).Gunner and Gwala (1994:230) cite an example:

Gunner and Gwala (1994:231) translated this war chant into English:

Leader: The bull came again!Credo Mutwa (1992:12) also uses a Zulu izigiyo in his play uNosilimela:

Ikhalaphi?Gunner and Gwala (1994:230) document this chant, too, although their documentation differs slightly from Mutwa’s in terms of spelling and punctuation. Gunner and Gwala’s last line also differs from Mutwa’s, reading "Ukuthi Ikhalaphi". Anyway, their English translation (1994: 231) of this izigiyo reads:

Where does it call from?Izibongo occupy a distinctive cultural space, and served a political function within the stratified Zulu monarchy (Brown, 1998:50). Izibongo in the ukugiya before a stick fight is understood in relation to izibongo recited at other occasions, but remains distinctly different from those. For detailed accounts of the various izibongo and discussion of their social significance, compare Gunner and Gwala (1994) and Brown (1998).

Izibongo in the ukugiya often link the fighter with a powerful animal. For example, Shaka’s izibongo often referred to him as lion or elephant (Brown, 1998:98). Izibongo can also associate a fighter with the heroic deeds of his ancestors (Leitch, Interview, 1996). These observations echo in the izibongo of Siyabonga Mzobe, recited by himself as an example of the manner in which his friends praise and encourage him during a stick fight:

Mzobe translated the praise as:

Small horns,The ukugiya is therefore a statement of the fighter’s own ethos; a statement of himself as warrior, a celebration of youthful masculinity, and a display of physical prowess that can include re-enactment of heroic battles of the past. The praise is not necessarily serious, but can include comic elements such as jokes and humorous physical actions intended to amuse onlookers (Leitch, Interview, 1996).

Although Gunner and Gwala (1994:1) point out that izigiyo and ukugiya are closely associated with "war and martial prowess", they add that in contemporary South African life, "they stress a potential rather than constant all-embracing link with war and the martial". Thus, the ukugiya is not performed exclusively as an introduction to physical conflict. Instead, it has transcended its historical roots to become a celebration of youthful masculinity:

The ukugiya is still performed before faction fights (Ntuli, Interview, 1996) and stick fights (Clegg, 1981:10). Its continued use in stick fights is perhaps in recognition of stick fighting as a form of symbolic warfare.

Following the performance of a ukugiya, the challenge takes place. Mbhense (Personal Communication, 1996) calls a challenge inselelo, or "I challenge you to fight".

The challenge is unambiguous and clearly distinguishable from the action. The challenge often involves the challenger slowly circling the fighting space while brandishing his shield, then bounding across the space up to the chosen opponent and shouting Nansi Inkunzi, or "here is the bull" (Derwent et al., 1998:63).

To accept the challenge, a man from the opposite party steps forward, and replies, "And here’s another bull" or nansen yinkunzi! Another reply to inselelo is woz’uzithane izinduku or "sticks understood" (Alegi, 1997).

Fighters do not rush into an attack after the challenge is accepted. Instead they square up and exchange blows to the shields, thus giving each other a chance to warm up to the situation. Stewart (Interview, 1996) believes that the warm-up also gives the fighters a chance to detect a weakness in their opponents’ defence.

The intensity of the action increases after the initial prodding, causing the fight to escalate (Fighting Sticks, Episode 1, [S.a.]). During this portion of the fight, the men consciously focus on the weak points of the opposition.

One of the basic rules of a stick fight is that stabbing is not allowed. (Zulu, Interview, 1996). In addition, a club or a stick with a knob is not used in a challenge match (Ntuli, Interview, 1996). Furthermore, if a fighter drops his stick, it is honourable to give him a chance to pick it up before resuming the fight (Fighting Sticks, Episode 1, [S.a.]). The main aim is to strike the opponent’s head (the action is termed ukuweqisa). Thus, all the blows delivered to the body attempt to create an opening in the opponent’s defence, in turn allowing the stick fighter to strike his opponent’s head.

Foul play includes hitting a man with your shield and tripping him (Zulu, Interview, 1996). If a man falls down, he should not be hit, but rather receive a chance to regain his composure before the fight continues (Fighting Sticks, Episode 1, [S.a.]). Frustration or weariness can motivate a combatant to cling to the opponent, or grab hold of him or his weapons. Such practices are inadmissible in a stick fight. Locking shields in the air can cause combatants to wrestle rather than stick fight, and should be avoided.

Although Ntuli (Interview, 1996) believes that techniques from other martial arts can be incorporated in a fighter’s technique, the consensus is that stick fighters should maintain the style of stick fighting by conforming to the techniques specific to the art. Stick fighters are thus concerned with the style of their discipline, and should not incorporate techniques foreign to the style as a means of defeating the opponent (Stewart, Interview, 1996).

A stick fight ends when one of the combatants is severely beaten or when the first blood is drawn (Stewart, Interview, 1996). The fighting is stopped by the inqwele (Ntuli, Interview, 1996), the induna (Mbanjwa, Interview, 1996), the warrior captain, or the elders (Fighting sticks, Episode 1, [S.a.]). According to Msimang (1975:166), combatants can also stop the fighting by exclaiming khumu, "it is enough", or maluju, meaning "hold it". The victor should accept the surrender with humility, as a "recognition of limit and self-restriction in spite of the moment of triumph" (Ndaba, Interview, 1996). Ndaba further points out that the victor should also take into consideration that the triumph is his, because of the opponent. As such, stick teaches participants sportsmanship, e.g., how to win or lose with grace.

The injuries sustained in a stick fight can be quite severe, and typically involve broken wrists and ribs (Leitch, Interview, 1996). First aid consists of placing cow manure (Shakaland, Home-video recording, 1996) or a handful of earth on a wound (Elliot, 1978:144). Should the victor have inflicted a wound on the loser’s head, he accompanies the loser to the river or any source of water, and helps him to wash his wounds as a token of goodwill (Leitch, Interview, 1996). Neither hostility nor resentment remains after a stick fight.

Although stick fighters never intend to kill a man in a stick fight, Mzobe (Interview, 1996) recalled how a small boy accidentally killed another with a blow to the temple. The inqwele was held responsible for the incident, and the small boy did not receive punishment. Clegg (1981:9) points out that adults are also not taken to court if a man is killed in a stick fight, but Mbanjwa (Interview, 1996) contradicts his statement.

8a. Inter-District Stick Fights (Umgangela)

8a. (1). Background

Under Zulu rule, KwaZulu-Natal was divided into various regions, districts, and inter-district areas under the rule of the king, chiefs, paramount chiefs, local chiefs, and headmen (Clegg, 1991:8). This traditional organisation was a fertile breeding ground for competition and rivalry. Feuds about the possession of land inflamed tension between leaders, and disputes over territory were settled by means of stick fighting (Leitch, Interview, 1996). Stick fighting was thus a method of defending a group’s territory, and asserting its boundaries.

Clegg, in reference to the Thembu clan of the Natal Midlands, argues that traditional districts were no longer practically in use after the arrival of European farmers in the late nineteenth century. Nonetheless, Zulus still operated within their traditional territorial boundaries. Limited offers of employment on the farms created further tensions regarding the occupation of traditional land among the indigenous people, perpetuating the practice of stick fighting into the present (1981:9).

Although such classical expressions of command and land distribution have officially been replaced by European structures, a strong sense of competition between traditional districts remains prevalent in the Natal Midlands (Clegg, 1981:8). Traditional leaders in KwaZulu still exert influence over their communities and competition between regional leaders is common (Zulu, Interview, 1996). The imaginary boundaries of traditional territories are still maintained as a "conceptual construct", or what Clegg (1981:9) terms "phantom districts".

While Clegg specifically directs his study towards the Thembu clan in the Natal Midlands, the notion of "phantom districts" is equally applicable to clans living in the Nongoma area. Zulu (Interview, 1996) identifies areas in and surrounding Nongoma with names different to the official names available. These "phantom" areas are further recognised by the appearance of landmarks and the characteristics of the landscape (Clegg, 1981:9; Zulu, Interview, 1996).

Clegg states that inter-district tensions were traditionally expressed during social rituals involved with the spring festival and weddings (1981:8-9). Schechner (1985:230) supports the origin of ritual in conflict:

Stick fighting serves as a social ritual that redirects the potentially dangerous interactions between people in hierarchical or territorial conflicts: "In the classic system these tensions [competition between districts] were expressed and contained in certain rituals. ...One of the most important elements in expressing and containing inter-district competition was theumgangela" (Clegg, 1981:8).

8a. (2). The Umgangela

The umgangela is a highly organised, "pre-arranged inter-district stick fighting match" with set rules. Clegg (1981:8) suggests that the umgangela as social ritual, although expressing a violent subtext, actually contains and controls the potential violence. Stick fighting thus "sublimates violence", in Schechner’s terms, providing a socially sanctioned release for aggression while strengthening and reaffirming the social fabric of the society. Stick fighting is thus an endless postponement of violence, enacting or channelling violence in such a way as not to endanger the immediate social environment. Potential antisocial impulses are transformed into an interactive and constructive process of socialisation.

The inter-district umgangela incorporates various layers of meaning within a well-known structure. Clegg (1981:9) states that such an umgangela takes place during the summer (e.g., between November and January). At an inter-district umgangela, men from the same region wear costume pieces to identify them as belonging to a certain region. Costume thus makes a statement about a group’s social solidarity, and can manifest itself in many forms, from sashes to hairstyles. Zulu (Interview, 1996) states that men from the same region should display something identical in their way of dressing for the event. Stick fighters of a region may take a collective name as a means of identification. Informants at Nongoma use the collective name Mshanelo, or broom, as a metaphor for fighting prowess (Zulu, Interview, 1996). Additionally, fighting sticks may be decorated to co-ordinate with the men’s clothing.

Three or four districts may be represented at the inter-district umgangela, forming "companies of men singing and shouting their war cries" (Clegg, 1981:9). The stick fight takes place on a predetermined space at an agreed date. Clegg explains that the war captains of the districts (known to each other) come together and lead the companies into rhythmic movements, thus displaying their district’s potential ability to conquer. They also make a symbolic statement about going into other districts and courting the sisters of the men in the conquered district.

Next, well-known stick fighters from each district break away from the group and perform their ukugiya, or ritual solo combat. Should a fighter do an impressive ukugiya, he is unlikely to be challenged. However, the ukugiya can also give clear indications of the shortcomings of a warrior’s technique or display habitual actions that provide clues as to how he can be beaten. As soon as a weakness is noticed, an opponent challenges the warrior by walking up to him during the course of the ukugiya (Clegg, 1981:9). In theory, normal etiquette applies, but Clegg (1981:9) mentions that inter-district stick fights can take place in long lines of 40-50 people (imigangela), where it is difficult to maintain the ethos of stick fighting.

8a (3). Spectators and Officials

Spectators are always present during stick fights to acknowledge what happened (Mbanjwa, Interview, 1996), and to judge if the fight was fair (Fighting sticks, Episode 1, [S.a.]). Although spectators play an integral role in the proceedings of a stick fight, they are not to interfere with the fighting.

Spectators consist mainly of men and young unmarried women in traditional attire (Mamthetwa as cited by Zulu, Interview, 1996). Men whistle, women ululate, and the spectators generally show a verbal appreciation of exciting actions (Zulu, Interview, 1996). The reaction of spectators can enhance the performance of the fighters, and the fight is followed with great enthusiasm (Leitch, Interview, 1996).

Although the duties of the warrior captains, or umphathi wensiswa, include maintaining order during the fights (Leitch, 1996), Clegg (1981:9-14) believes that the umgangela cannot contain the tension between the districts. This can lead to violent encounters; hence the development of the isishameni style of dancing, which is today a more socially acceptable expression of conflict in KwaZulu-Natal. Leitch (Interview, 1996), with reference to KwaZulu, is of the opinion that the escalating violence in contemporary Zulu society is a direct result of the decline in the practice of stick fighting. Faction fighting can be seen as a modern manifestation of tensions between parties, but is by no means an acceptable method of resolving conflict through physical interaction (Ntuli, Interview, 1996).

The ritual combat of an umgangela is significantly different from faction fighting, during which induku and ubhoko are utilised as real weapons. Moreover, faction fights are not governed by the same rules as a stick fight: in faction fights, the intention is to cause harm and the fight erupts as an expression of aggression (Ntuli, Interview, 1996).

Leitch (Interview, 1996) indicates that since there is little restraint on the use of weapons in a faction fight, participants are not restricted to the use of induku and ubhoko. In contrast, Zulu (Interview, 1996) emphasises that no "meanness" should be involved in district fighting; the umgangela is an opportunity for "playing" and "peaceful fighting", and determining who the best fighter in the region is.

Ntuli (Interview, 1996) recalls that in his youth, "tribal wars" in the Gingingdlovo-Dokodweni (KwaZulu) area assumed the form of a stick fight.Regional stick fighting is still prevalent today in the Nongoma area (Zulu, Interview, 1996). Stick fights between people of Mtunzini and Durban also take place (Mbanjwa, Interview, 1996), although traditionally stick fighting was not as prominent in Natal as in KwaZulu (Clegg, Personal Conversation, 1996).

In any event, faction fights are armed brawls, whereas inter-district stick fighting is consciously a game, loaded with symbolism familiar to both the fighters and the observers.

8b. (1). Introduction

Most societies have rites of passage that are regarded as the "passport to adult status" (Elliot, 1978:142). Mlotshwa (1988:5) states that such rites of passage indicate the transition from one set of socially identified circumstances to another. They are concerned with personal development, and include the celebration of transitional stages in life such as birth, puberty, marriage, and death.

In Zulu society, the thomba or male puberty ceremony marks the "attainment of physical maturity, and the occasion is a very important one both for the individual and for his kraal [village]" (Mahlobo & Krige, 1934:166). Elliot (1978:142) is of the opinion that a puberty rite is not only significant in terms of its social function, but is also pivotal in a young man’s spiritual development. Stick fighting is a prominent element of male puberty rites, and so forms part of the symbolic passage of a male to the adult world. However, since Mahlobo & Krige (1934:166-181) analyse the thomba ceremony in detail, for the purposes of this article, a brief overview of selected aspects of the ceremony is all that is necessary.

The thomba ceremony starts after a boy experiences his first nocturnal emission, thus providing concrete evidence that he is entering a new phase of his life (Elliot, 1978:143). The boy follows a customary, set procedure to announce the event publicly. Firstly, he gets up before dawn, secretly steals his father’s cattle, and drives the herd to a place where they will not be easily located. The father, on noticing the missing cattle and son, announces the news and prepares the appropriate intelezi for the event. Secondly, the boy’s peers follow the example of stealing their fathers’ cattle and join the cattle with the stolen herd. As soon as the boy is found, the area around his stomach is smeared with "crab mud" and he must swim in nearby water (Mkhonza, 1984:19). Thirdly, the cattle must be found. Although Elliot (1978:143) acknowledges that differences exist among various clans, the observation provided is in accordance with the account given by Bryant (1949:654).

According to Elliot (1978:143), the first attempt to reclaim the cattle involves sending girls of the local kraals to return the boys and cattle home. Both girls and boys carry sticks and shields, and a stick fight erupts between the sexes. Gender roles are clearly delineated in the Zulu society, and stick fighting belongs to the sphere of the man (Ndaba, Interview, 1996). Since the socially ascribed gender role for women does not include warfare or martial arts (Ndaba, Interview, 1996), it is highly unusual to find instances where women wield the sticks. The thomba ceremony serves as an example of such an exception to the rule.

The fight presumably takes place in the space selected to hide the cattle. Elliot (1978:143) insists that the girls observed were experts with the fighting sticks, although they were eventually beaten in combat by the boys and chased home. Bryant, however, describes quite a different outcome of events:

Ritter (1957:16) states that both sticks and switches were employed in such a battle. Elliot (1978:143) argues that whipping switches were traditionally used, but were replaced by fighting sticks. On the supposedly rare occasion that the girls won, the boy reaching puberty was labelled a weakling (Elliot, 1978:143). Mahlobo & Krige (1934:157-1181) do not give an account of any practice similar to the fighting girls. It is thus difficult to determine whether the custom has its origin in ancient traditions, or whether it is a relatively modern development. Leitch (Interview, 1996) maintains that it is very seldom that girls fight the boys at a contemporary thomba ceremony, due to the decline of attention to the intricate details of the ritual.

If the girls did not succeed in recovering the stolen cattle, the fathers of the kraals go to fetch their cattle and boys. A stick fight between the boys and the men then takes place, usually with devastating consequences for the inexperienced boys. Once back at home, the boy undergoing the thomba ceremony is given intelezi and beer drinking begins. Further rituals take place over a number of days, and throughout the rest of the ceremony, the boy is constantly instructed on the appropriate patterns of social behaviour (Elliot, 1978:144).

It appears that participants in the ceremony are fully aware of the symbolic nature of their interactions. Furthermore, the playful subtext of the fighting actions is evident at all times. The boys are presumably engaged in sparring rather than actual stick fighting.

8b. (3). The Iphapu (Lung) Festival

During the iphapu (lung festival), stick fighting manifests itself in a highly organised format (Schoeman, 1982: 51).

Schoeman explains that participation in the iphapu festival is the sole privilege of herd boys. Herd boys are unmarried men and boys ranging in age from about 7-25 years. When a kraal slaughters a cow, certain parts of the beast are reserved for the herd boys only (1982:48). These parts include the heart, lungs (iphapu), and smaller fleshy parts of the animal such as the ears, spleen, and upper lip (Msimang, 1975:167). The lungs and the best meat received are not eaten in the kraal, but are taken away by the senior boy to a space specifically selected for the lung festival (Schoeman, 1982:48).

Strict criteria govern the selection of a suitable space. Schoeman (1982:48) identifies some of the determining factors. Firstly, the space should be located in an area high enough to keep a watchful eye on the surrounding area and possible enemies. Secondly, the space chosen should accommodate the need for privacy and safety of participants. Msimang (1975:166) points out that the area should be suitably private to play the game of stick fighting without being disturbed by the women of the kraal. Thirdly, a substantial amount of rocks should be available. The rocks are to be shifted around in order to produce a sound that is clearly audible throughout the surrounding area.

The sound functions as an invitation to the iphapu festival for other herd boys of the area. The boys drive their herds of cattle in the direction of the sound, and once assembled at the designated space, the younger boys are sent to collect wood for a fire. The boys barbecue the lungs, cut them into pieces, and distribute the pieces for consumption among the participants. Meanwhile, the izingqwele (senior boys) stuff the pleura with choice meat. The pleura are barbecued exclusively for the ingqwele (leader of the herd boys), and juniors only get a taste if a piece of the meat is offered to them as a reward for courage or bravery (Schoeman. 1882:48-49). Next they barbecue the heart of the animal, cut it to pieces, and divide the meat between the izingqwele (senior herd boys). Schoeman (1982:49) clarifies the action by providing a technical description of the procedure involved in eating the heart.

During the iphapu ceremony, juniors can challenge the leadership of their seniors. Boys from throughout the area gather to witness a challenge and acknowledge the victor as leader (Msimang, 1975:166). A challenge occurs within an accepted structure of events. Placing fat from the piece of lung reserved for the izingqwele on a stick and daring boys to take it away and eat it constitutes a challenge. The senior is expected to accept the challenge. Boys other than the most senior can turn down or ignore a challenge, unless the challenge is directed toward them by name, but by doing so, they acknowledge the current izingqwele as the undisputed leader (Schoeman, 1982:50-51). The izingqwele can also invent a reason for a youngster to go and see if all is well with the cattle. Upon his return, the youngster is told that another boy made inflammatory statements about him, or about his mother’s private parts. The statements might well have been made, but are very likely a fabrication. In either case, the boy is morally obliged to accept the challenge and initiate a fight.

A stick fight at the iphapu festival continues until a combatant emerges as the victor (Schoeman, 1982:50-51) or until one of the pair exclaims "khumu!" (Msimang, 1975:166), meaning, "It is enough". The spectators are fully involved in the fight, and the participants are enthusiastically encouraged and well-executed blows receive praise. Afterwards, the victor receives praise and applause from the whole congregation of boys, while the loser is subjected to playful jests and laughter.

Organised raids on the herds of cattle belonging to neighbouring kraals also take place during the lung festival. The intention of these raids is never to steal cattle. Instead, the intention is to create a playful scenario that provides a motivation for a stick fight.

These cattle raids have the potential of involving a large number of boys and young men in what is essentially a game of tactics. Firstly, a group of spies is selected from the younger boys participating in the festivities. The spies are then dispatched to establish when and how the raid will take place. The ingqwele may even accompany the boys on this expedition. Secondly, the cattle are brought to the grazing fields of the attackers. When the cattle are found missing, the victims arrive en masse to claim back their cattle, with the result being a stick fight. Should the victims lose the stick fight, then their cattle are not returned to them. Instead, they have to seek the assistance of older men, who negotiate with the attackers. The older men are supposed to be embarrassed by the actions of the youngsters, and will scold them thoroughly before attempting to retrieve the cattle. The cattle are given back to the men immediately upon their arrival, and the victims return home while enduring joking remarks from the attackers (Schoeman, 1982: 49-52).

After engagement in the necessary action, the cattle thieves return to their home kraal, where the rest of the meat (ears, lip and spleen) is eaten and washed down with Zulu beer (Msimang, 1975:166). It is highly probable that yet another fight between groups of boys will erupt after the general feasting back at home.

Schoeman (1982:52) claims that the highly structured and hierarchical nature of the programme gives rise to an almost political organisation among the herd boys. Authority flows down from the senior ingqwele to the izingqwele, and from the izingqwele to the ordinary herd boys. The organisation, the power structures, and the negotiations required following cattle raids are simply reflections of the power structures existing in the wider community.

8c. Courtship

Traditional Zulu courting custom dictates that a boy should discover where the girl he admires collects water, and "waylay" her on her way to or from the water. A girl, or intombi, can accept or reject the boy’s advances by changing her customary route to the water. Should she have another admirer, then the boys may test their skill in stick fighting in an attempt to win her favour (Stewart, Interview, 1996). Ntuli (Interview, 1996) points out that the girl would always be present to observe the outcome of such a fight.

According to Stewart (Interview, 1996), the outcome of this contest might further develop into a fight between two groups of boys. This is most likely to occur if the loser is seriously aggrieved, or wishes to challenge the outcome of the fight. The loser will inform his friends about the fight, and provide a handy excuse for his weak performance. The loser’s friends might well be aware that the excuse is fictional, since it is generally accepted that the better stick fighter should win a stick fight. However, they willingly suspend their disbelief in order to have an opportunity to stick fight. The victor anticipates the loser’s actions, and in turn, notifies his friends about the fight that took place. Both parties then patiently wait for an appropriate opportunity (such as a wedding) to engage in a clash of arms, one party to restore its friend’s honour and impress the intombi, the other to again prove its superiority and impress the intombi.

Ntuli (Interview, 1996) believes that many stick fights are caused by rivalry for female attention. Stewart (Interview, 1996) points out that should a boy be too shy to confront a girl with his amorous advances, his sister or a female friend can come to his assistance and court the girl on his behalf. The female will dress in male attire, complete with induku, ubhoko, and ihawu. She might display arrogance or aggression (associated with masculine behaviour), and might even stick fight, although not to the extent that a boy would.

Additionally, a young man or boy might carry a stick heavily decorated with beadwork as an indication that he is interested in a particular girl. The stick is not utilised for fighting purposes, although it is carried with his fighting sticks (Shakaland, Home-video recording, 1996).

A Zulu wedding is a public event that takes place over a period of about three days (Dalrymple, 1983:121). It involves specific rituals in various stages of the ceremony that Dalrymple (1983:121-194) and Bryant (1949:533-604) have described in detail. Therefore, I will only pay attention to the role that stick fighting plays in the occasion.

Nowadays stick fighting often takes place before a wedding ceremony to settle any disputes between parties (Larlham, 1985:6). However, Mbanjwa (Interview, 1996) and Dalrymple (1983:131) indicate that stick fighting can also take place after the wedding ceremony. For example, the last afternoon of the wedding observed by Dalrymple (1983:121-131) concluded with older men drinking beer in the cattle enclosure while younger men fought with sticks.

Ntuli (Interview, 1996) indicates that stick fighting is an expected part of a Zulu wedding, and that participants will engage in a fight even if there are no disputes to be settled. Accordingly, men attend the wedding fully prepared for a stick fight. Young men might also decorate their bodies and their hair with beadwork, or dress up in beautiful pants and string vests to impress the girls present. Mzobe (Interview, 1996) notes that to this day, Zulu men often dress in traditional attire for a wedding, and even hire the appropriate clothes if they do not possess their own.

Stick fighting takes place at a wedding to impress the girls and to build a reputation as a stick fighter of calibre (Leitch, Interview, 1996). A man might even pretend to be interested in another man’s girlfriend to provoke a fight (Shakaland, Home-video recording, 1996). Alternatively, a man might intentionally overdress and appear very arrogant in order to anger other men (Stewart, Interview, 1996).

It seems that people at the wedding are aware of the playful dynamics operating in the attempts to provoke a stick fight, and go along with the game. Zulu (Interview, 1996) sees a wedding as an opportunity to "play umgangela", suggesting that the action is not an overly serious competition between men.

As always, a suitable space for the fighting is selected. This space must be in view of the wedding party, but not disturbing the proceedings. The warrior captain chooses the ground, usually situated on a hillside that overlooks the wedding. (Although level ground is preferable, steep slopes will not prevent a stick fight from taking place.) The place at which a stick fight happens is termed umgangelo, and spectators delineate its space by forming a human circle big enough to accommodate the action (Leitch, Interview, 1996).

To ensure correct protocol, the fighting takes place under the supervision of the warrior captains or leaders of the group. There is a specific structure in the flow of events. Firstly, people gather around the selected space and the men take turns to ukugiya. Larlham (1985:6) states that the performance of a ukugiya serves as a challenge to any man who wishes to display his prowess as a stick fighter. Dalrymple (1983: 160), however, indicates that a person who disrupts an ukugiyaat a Zulu wedding risks a stick fight. After the performance of a ukugiya, the challenge takes place.

Mzobe (Interview, 1996) points out that a man could challenge another by teasing him. At his sister’s wedding in 1995, Mzobe’s peers jokingly remarked that his lean physique would hinder him in a stick fight. Mzobe accepted this challenge in an attempt to prove his fighting skills. The challenge is unambiguous and clearly distinguishable from the action.

To begin the stick fight, a man from the opposite party accepts the challenge by taking a step forward. The resulting fight can incorporate comical elements designed to entertain the spectators and infuriate the opponent (Leitch, Interview, 1996). The reactions of the spectators vary according to the course that the fight takes. The spectators exclaim their delight at a good manoeuvre and watch quietly as the fight grows serious. Ululating girls assist in building the excitement, and perform their stamping dance (ukuggiza) (Larlham, 1985:8), thus encouraging the fighters to prove their superiority at stick fighting. As soon as a man is defeated, another from the opposition takes the stage. A great number of men can partake in the stick fighting depending on the following of the bridal parties (Stewart, Interview, 1996). Leitch (Interview, 1996) indicates that five or six hundred men can be engaged in the fighting, without any fatalities occurring.

Stick fighting at weddings has been discouraged of late, due to the serious nature of the injuries that might occur. Mafisa (Personal Communication, 1996) states that stick fighting at Zulu weddings is no longer a common practice, and only occurs in the rural areas.

9. Conclusion

Traditional stick fighting, as performed in the rural areas of

KwaZulu-Natal, continues to serve as a process of socialisation, and to transmit

the social norms of the community in which it operates. In recent years, stick

fighting has become politicised to the extent that this practice, which once

played an instrumental role in building the pride of the Zulu nation, has come

to be regarded with contempt or suspicion by some. Contemporary practices of

stick fighting such as occurs in the hostels of mines, in the parks of

Johannesburg, or in the competitive team sport played by men travelling to

countries such as Japan, is a faint echo of the art’s traditional richness and

social importance. In a country historically associated with the violation and

exploitation of indigenous cultures in all spheres of life, vibrant arts such as

Zulu, Pedi, Xhosa, Sotho or Ndebele stick fighting are long awaiting the

recognition and respect that these arts deserve: fighting arts that are uniquely,

and proudly, South African.

Bibliography

ALEGI, P. 1997. Umlando Wemidlalo Emasendulo Eningizimu Afrika: The pre-colonial origin of soccer’s popularity in modern South Africa.http://people.bu.edu/palegi/imidlalo.html.

BECKER, P. 1964. Rule of fear: the life and times of Dingane king of the Zulu. London: Longmans.

BOFANA, M. 1997. Personal communication by Monica Bofana, domestic worker, Goedgedacht farm, Fochville, South Africa, January 29.

BROWN, D. 1998. Voicing the text: South African oral poetry and performance. Cape Town: Oxford University Press.

BRYANT, A.T. 1949. The Zulu people: as they were before the White Man came. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shooter.

BUTHELEZI, V. 1996. Interview with Vusi Buthelezi, Herbalist, Dumazulu, South Africa.

CLEGG, J. 1981. Towards an understanding of African dance: the Zulu isishameni style. Unpublished paper, Symposium on Ethnomusicology, Rhodes University.

CLEGG, J. 1996. Personal telephone communication by Johnny Clegg, University of Zululand.

DALRYMPLE, L. 1983. Ritual performance and theatre with special reference to Zulu ceremonial. MA thesis, University of Natal, Durban.

DERWENT, S. Leitch, B., De La Harpe, R., and De La Harpe, P. 1998. Zulu. Cape Town: Struik Publishers.

ELLIOT, A. 1978. Sons of Zulu. Johannesburg: Collins.

GUNNER, L. & GWALA, M. 1994. Musho: Zulu popular praises. Second edition. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press.

KAVANAGH, R. M. (ed.). 1992. South African people's plays: ons phola hi. Johannesburg: Heinemann.

KRIGE, E. J. 1965. The social system of the Zulus. Second edition. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shooter.

KROG, A. 1994. Stokveg. Die Suid Afrikaan, October: 42-43.

LABAND, J. 1995. Rope of sand. Jeppestown: Jonathan Ball Publishers.

LARLHAM, P. 1985. Black theatre, dance and ritual in South Africa. Michigan: UMI Research Press.

LEITCH, B. [S.a.]. Fighting sticks. Video. SABC Production.

LEITCH, B. 1996. Zulu stick fighting. Personal interview. Umhlali, South Africa.

MAFISA, T. 1996. Personal communication by Tankiso Mafisa, Honours student, University of Zululand.

MAHLOBO, G.W.K. & KRIGE, E.J. 1934. Transition from childhood to adulthood amongst the Zulus. Bantu Studies, VIII (2), June: 157-191.

MBANJWA, M. 1996. Zulu stick fighting. Personal interview. Mtunzini, South Africa.

MBHENSE, D. 1996. Interview with Dumisani Mbhense, third year student, University of Zululand.

MKHONZA, M.F. 1984. A brief analysis of Zulu drama. Honours thesis, University of Zululand.

MLOTSHWA, N. 1984. A study of diverging and converging points between ritual drama and contemporary drama with special reference to Zulu rituals. Honours thesis, University of Zululand.

MNQAYI, P. 1998. Ukungcweka. Personal explorations. University of Zululand.

MSIMANG, C. 1975. Kusadliwa ngoludala. Pietermaritzburg: Shuter & Shooter.

MUTHWA, C. 1992. uNosilimela. In: Kavanagh, R. M. (ed.). South African people's plays: ons phola hi. Johannesburg: Heinemann: 5-61.

MZIMELA, B.M. 1990. A brief survey of Zulu warfare vocabulary and its literary contribution to the Zulu language. Unpublished research essay, University of Zululand.

MZOBE, S. 1996. Zulu stick fighting. Personal interview. University of Zululand.

NDABA, J. 1996. Zulu stick fighting. Personal interview. University of Zululand.

NTULI, J. H. 1996. Zulu stick fighting. Personal interview. University of Zululand.

POOLEY, E. 1993. The complete field guide to the trees of Natal, Zululand and Transkei. Durban: Natal Flora Publications.

RITTER, E. A. 1960. Shaka Zulu: the rise of the Zulu empire. London: Longmans.

SCHECHNER, R. 1985. Performance studies. London: Routledge.

SHAKALAND. 1996. Zulu stick fighting. Home-video recording.

SCHOEMAN, H.S. 1982. Spel in die kultuur van sekere Natalse Nguni. Pretoria: Universiteit van Suid-Afrika.

SOTHO, Lebhulo. 1997. Personal observation, Goedgedacht farm, Fochville, 29 January.

STEWART, G. 1996. Zulu stick fighting. Personal interview. Hluhluwe, South Africa.

TYRELL, B. & JURGENS, P. 1983. African heritage. Johannesburg: Macmillan South Africa.

WERNER, A. 1933. Africa: myths and legends. London: George G Harrap & Co.

ZULU, M. 1996. Zulu stick fighting. Personal interview. Nongoma, South Africa.

Information was also obtained by observing informal stick fights whilst based at the University of Zululand (1994-2000).

Endnotes

EN1. Providing Western names for these trees is problematic, as amongst other difficulties, the names vary according to regions and dialects. uMquambathi, or protea roupellia, is commonly known as the silver sugarbush. It is found in Zululand and the Transkei (Pooley, 1993:86). uMazwende, or artabotrys monteiroae, is commonly found in northern Zululand, where it is known as the red hook-berry tree (Pooley, 1993:94). uMazwende can also refer to the uMazwende-omlhope tree, or monanthotaxis craffa, which is renowned for its magical properties. This latter tree is commonly called the dwaba berry (Pooley, 1993:94). The ibelendlovu tree, kigela africana, is popularly identified as the sausage tree. Its wood is not very hard, but it is tough (Pooley, 1993:94). uMphahla is a tree from the Brachylaena species, and umthathe or ptaeroxylon obliquum is generally referred to as the sneezewood tree (Pooley, 1993:448). Available Western botanical resources do not list uMunquma.

EN2. The induku is also called umshiza, umzaca, isikhwili, isiqwayi, imviko, and umqambathi, depending on the regional discourse (Mzimela, 1990:21). For example, informants in Nongoma favour the name isikhwili, while informants in Mtunzini and Hluhluwe favour the name induku.

EN3. The action of striking with induku can be called ukugadla, ukushaya, ukubhonya, ukuqunsula, or ukuvithiza (Mzimela, 1990:21).

EN4. uPhindamshaye, or the adenia gummifera, is a poisonous climber often used for medicinal purposes (Pooley, 1993:338). The phind’umuva is an unfamiliar species of plant, identified as a creeper by Buthelezi (Interview, 1996). Cene seems to be a generalised term indicative of a number of small aloes.

Dr. Marié-Heleen Coetzee lectures at the drama department of the University of Pretoria in stage movement, educational drama and theatre, and drama and film studies. She was previously on faculty at the University of Zululand (1994-2000). Whilst based in Zululand, her research focused on the cultural-anthropological and physical dynamics of Zulu stick fighting and its application to theatre. Most of her research on the cultural-anthropological aspects of stick fighting was conducted and documented between 1995-1996 as part of the research project "Playing Sticks: An Exploration of Zulu stick fighting as performance". She has addressed national and international conferences on her field of study, taught at national and international stage combat workshops, and published academically. Additionally, she has directed, performed in, and choreographed various theatrical productions. She serves on the executive board of the South African Performers’ Voice and Movement Educators (SAPVAME) and on the Artistic Advisory Committee of the International Organisation of the Sword and the Pen (IOSP). She initiated and organizes the annual "Rendezvous South Africa!" international stage combat workshops.

Untying The Past. Rapping Up The Present. Preparing The Future

BONA Magazine – December 1988 http://www.3rdearmusic.com/reissue/siphomchunu.html

By AMOS MNGOMA - Photographs by DAVE ELLINGER (P)© BONA 1988

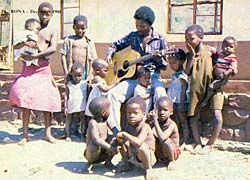

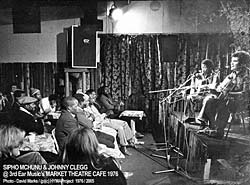

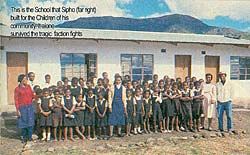

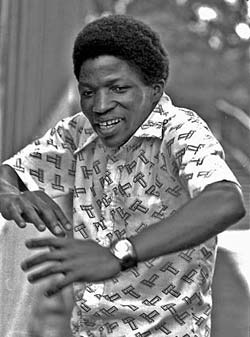

Sipho Mchunu is a brave man. Two years ago he broke with partner Johnny Clegg to be with his large family and to till the soil. Juluka was no more.

During that period he saw just about everything he had worked for go up in flames. He also saw Johnny Clegg and his new group, Savuka reach great heights in the music world both locally and overseas.

Sipho is brave. After all the trials and tribulations that befell him, he's decided to make another go of his musical career.

Slowly the Mchunu family has pieced together their lives, and Sipho feels the time is right for a comeback. "I'm going for traditional music”, he said. "I want to give my friends here and overseas the real African message, deep from the roots of our tradition, not just a meaningless mixture of African / Western beat.